A Market-Driven Approach to AI and Workforce Transformation (Part 2)

How the AI revolution demands a return to uniquely human skills - and what policy can do to help us get there

Welcome to all our new readers! This post is part of our new series on AI & Labor—a space to explore how intelligent machines are reshaping the very nature of work.

Over the coming weeks, we’ll continue to share insights on how AI is transforming labor markets—led by our Labor Policy predoctoral researcher, Revana Sharfuddin.

Author’s note: This is Part II of a two-part essay on preparing for the AI-augmented economy. In Part I, I focused on the coming labor transitions and how to think beyond automation toward augmentation. In this second installment, I dig into what readiness really means—not just as workers, but as people. Not just for the economy, but for society. Readiness is not simply a matter of skills; it’s a matter of meaning. As Tyler Cowen recently argued, we’re entering a future where flourishing will require a radical shift in how we view purpose, collaboration, and value.

Preparing for that future means confronting a series of cultural, institutional, and policy challenges. It will require mindset shifts at the individual level, renewed collaboration between companies and civil society, and smarter policy that removes roadblocks rather than creating new ones.

We Need Each Other: Working Together, Resting More, Rebuilding Society

Since the rise of the internet and the IT revolution, we have been living in the era of the technical elite, where technical skills have reigned supreme. The message has been clear: master coding, data analysis, and computational thinking, and you will thrive. Soft skills—like communication, collaboration, and emotional intelligence—have often been sidelined as secondary. Even in team-based fields like software development, direct interpersonal interaction has been reduced to virtual workspaces where developers collaborate through shared screens and chat channels, creating digital systems with minimal face-to-face interaction.

But perhaps it is time to step back and reconsider what we have left behind.

As coding and automation-related jobs surged during the computerization boom, professional skills that emphasize relationship-building, collaboration, and emotional intelligence were systematically devalued. The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated this shift, particularly for younger workers whose first jobs were fully remote. Workplace networking, mentorship, and informal social learning—once essential for professional growth—were suddenly absent. Dating and friendships, which once flourished through organic, in-person interactions, became mediated almost entirely through screens. A generation of workers entered adulthood without developing the soft human capital that underpins trust, adaptability, and social cohesion.

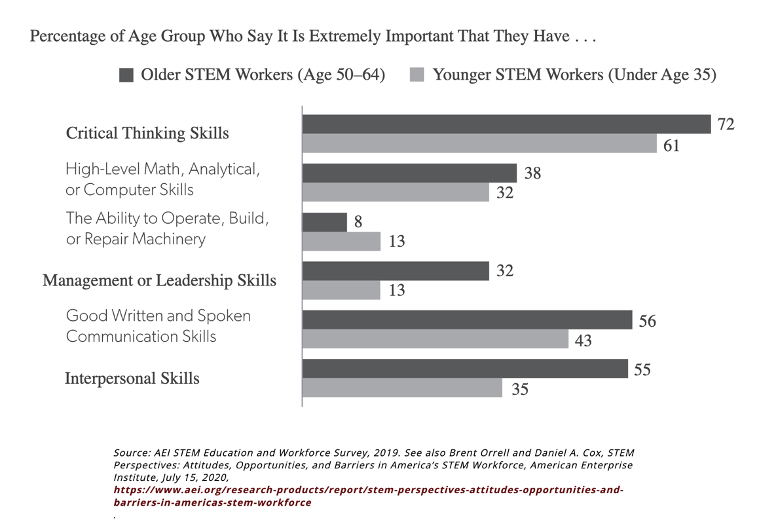

Survey research shows that valuing interpersonal skills has the largest generational gap, with older STEM workers valuing them far more than younger ones.

For many, remote work became a convenient escape from the often exhausting unpredictability of human interaction. And understandably so—social engagement takes effort. It requires learning each other’s rhythms, making space for different personalities, navigating rapidly shifting social norms, and granting others the benefit of the doubt. In an age where a single misplaced word can trigger outrage, where conversations feel like navigating a minefield of political correctness, and where miscommunication is met with instant dismissal rather than understanding, it is no surprise that many have opted out.

The result? A loneliness crisis, increasing political polarization, and a workforce that has learned it is simply more efficient to work from home, alone, free from the complications of human interaction.

But in optimizing for efficiency, have we sacrificed something fundamental? Have we, in the process, lost a bit of what has historically been our greatest comparative advantage—being human?

To be clear, remote work offers undeniable benefits—it allows for greater flexibility, more time with family, and better support for caregiving, all of which are crucial in an era of declining fertility and weakening social cohesion. But as we weigh these advantages, we must also consider what we risk losing. Technology has consistently freed up time from routine labor, yet whether that extra time enhances our lives depends on how we use it.

Consider this striking statistic: In 2015, an average U.S. worker could have maintained the income level of an average worker in 1915 by working just 17 weeks per year. AI has the potential to accelerate this trend—reducing time spent on repetitive tasks and increasing leisure to allow for a greater focus on family life, child-rearing, and deeper interpersonal relationships. However, the full benefits of this shift can only be realized if we lean into our comparative advantage as humans.

History shows that the jobs that endured were those that leveraged human strengths—judgment, creativity, and social intelligence. If AI is poised to take over routine technical tasks, the real opportunity lies not in competing with machines but in mastering the distinctly human skills that allow us to wield AI to its fullest potential.

Taxing the Future? Unpacking the Risks of AI Penalties

For decades, conventional economists have made a critical mistake: underestimating the burden placed on workers displaced by technological shifts and globalization. Foundational economic models assumed that technological progress was neutral, benefiting all workers. In practice, technological change can disproportionately help some while displacing others in the transition period. While advancements boost productivity and raise overall living standards, they do not always distribute their gains equally.

Too often, the response has been cold rationalism: Your job is obsolete? Adapt or risk being left behind. But economic agents are not just anonymous data points in a labor market model. They are people, with families, financial obligations, aspirations, and identities deeply tied to their work. The assumption that displaced workers can “easily” retrain and transition “seamlessly” into emerging fields ignores the real costs of career shifts. Middle-aged and low-wage workers face steep learning curves, financial constraints, and cognitive exhaustion from balancing work, childcare, and financial stress.

The lower a worker is in the income distribution, the more cognitive capacity is consumed by immediate survival concerns—worrying about bills, rent, and daily necessities—leaving little capacity for retraining or investing in new skills. When these realities are ignored, trust in institutions erodes.

Political polarization is, in part, a cautionary tale about the consequences of dismissing economic displacement. When workers are told that the economy is better off on average, while their own prospects remain bleak, it breeds disillusionment and a sense that the system no longer represents them.

In recent decades, many market-oriented economists have largely remained silent about proactive solutions for supporting workers amid technological disruptions. This absence has allowed other groups to step forward with proposals—mostly centered on taxation or redistribution. Consider, for instance, a recent policy memo by Acemoglu and his colleagues suggesting taxes on AI technology.

While their recommendation emerges from rigorous, influential research, we must examine carefully the assumptions underlying their proposals. In traditional growth frameworks, such as the Solow or Ramsey–Cass–Koopmans models, technological advancement is modeled explicitly as labor-augmenting productivity—captured by a parameter. In these scenarios, technological progress complements workers uniformly, enhancing productivity without replacing jobs.

Of course, this is a simplification—real-world effects are uneven, and some degree of substitution between labor and technology does occur, depending on the task. However, Acemoglu et al.'s task-based model differs fundamentally. Their framework explicitly addresses automation—where technology replaces labor—without an exogenous aggregate productivity shifter. In other words, the economy evolves as tasks shift between capital and labor, not by scaling up labor productivity.

Consequently, their optimal tax calculations are primarily aimed at addressing cases of marginal ("so-so") automation, where AI substitutes for human work without meaningful productivity improvement.

If we broadly apply an optimal tax rate designed for labor-replacing AI to all AI technologies—including those that enhance human capabilities—we risk penalizing the very productivity gains essential for wage growth and job creation.

Time and again, history has taught us that the best way to support displaced workers is through retraining programs. But who will lead this effort? The answer is almost always the government. Yet do we really trust policymakers to understand, predict, and effectively respond to one of the most complex technological transformations in modern history? Consider the now-famous congressional hearing where TikTok CEO Shou Chew testified before the House Committee on Energy and Commerce—a moment that starkly illustrated how disconnected many policymakers are from even the most basic workings of technology. If these are the same institutions we expect to guide workers through the AI revolution, should we not be thinking more critically about alternative solutions?

Two Market-Based Reforms to Support a Changing Workforce

While comprehensive solutions will require broader effort, here are two practical reforms that could help us begin moving in the right direction:

First, fix how the tax code treats investments in human capital. Currently, businesses can deduct expenses for worker training only if the training improves skills for their current job—not if it qualifies them for new types of work. This creates a perverse incentive: companies have a tax advantage when training workers to stay in the same roles but a disincentive when investing in training that allows employees to transition into higher-value, future-proof jobs. If we treated worker training the same way we treat equipment purchases—allowing businesses to fully deduct all training expenses—firms would have a stronger incentive to invest in reskilling their workforce. Unlike industry-specific tax credits, which introduce complexity and distort incentives, full expensing of all forms of investment—both human and physical capital—ensures neutrality and efficiency.

Second, embrace a universal form of Individual Training Accounts (ITAs)—a worker-centered approach designed to empower job seekers by letting them choose training that aligns with their interests and market demands. However, an even more impactful approach to meet the same goals would be the adoption of Universal Savings Accounts (USAs). Compared to ITAs, USAs are simpler, more flexible, and easier for individuals to manage on their own. Many low-income families struggle with navigating numerous tax-advantaged savings accounts, each with distinct eligibility requirements and penalties. This cognitive burden discourages savings and undermines financial security, particularly for those most vulnerable. USAs simplify the process by offering a single, accessible savings account where contributions grow tax-free and withdrawals can be made at any time, without taxes or penalties. Experience from Canada and the United Kingdom shows this simplified approach increases savings participation among low-and moderate-income families, giving workers the agency, dignity, and self-determination they need to invest in their own futures.

Building Coalitions: Why We Need Everyone at the Table

A shift of this magnitude demands collaborative effort—businesses, workers, policymakers, and civil society must all be at the table because the stakes are too high for complacency. Recall my earlier discussion in Part I on the business potential of automation versus augmentation (as illustrated by Erik Brynjolfsson). History shows that automation alone has limits, while augmentation—when coupled with structured retraining—has the power to unlock immense economic dynamism. Companies must take the lead in human capital development because augmentation builds stronger workforces, reduces displacement anxiety, and creates the foundation for shared economic growth.

Private industry needs to be proactive—not just funding retraining but shaping it. Companies should partner with local community and technical colleges to design micro-credential programs that match regional labor market needs. Just as important, they should help workers navigate these options through clear communication and guidance. Training tied to local demand, clearly communicated, is how anxiety about obsolescence can become ambition for what's next.

The momentum is already building. Since my last Substack post, I was invited to share my research with members of Capitol Hill staff. I am happy to report that there is growing bipartisan interest in supporting workers and communities amid technological change. Additionally, the newly launched AI-Enabled Policymaking Project (AIPP) has convened AI labs, startups, civil society organizations, academic experts, policymakers, government representatives from defense and intelligence, and independent technologists to share specialized knowledge and identify practical solutions. Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) are also proactively engaging researchers to integrate AI into their workflows. Today, I'll join the Fairfax County Small Business Forum to further these important conversations.

Public-private partnerships are essential, but equally important is a thoughtful reimagining of the labor unions’ role. Unions should no longer be seen merely as relics of industrial-era conflict or obstacles to innovation. Instead, they can serve as strategic partners—helping businesses and workers navigate change, supporting effective retraining, representing worker voice, and fostering shared understanding of future market directions. Union involvement in the SB 1047 debate signals a willingness to engage constructively in shaping AI’s role in the economy. However, for unions to realize their full potential, a reorientation is necessary—reforming institutional laws and structures, shifting away from traditional adversarial approaches toward collaboration, and embracing the possibilities of augmentation rather than opposition.

In the United States, existing labor laws grant certified unions exclusive bargaining rights, which can inadvertently encourage more adversarial stances. In our new paper, we explore alternative institutional structures that could enable unions to evolve into collaborative, forward-thinking partners, fostering constructive dialogue and cooperation between workers and firms. This shift can transform AI from a perceived threat into a catalyst for economic growth and shared prosperity.

Conclusion

The lesson from history is clear: when societies harness technological change rather than fear it, they emerge stronger. But achieving this strength requires purposeful action. It demands individuals willing to revalue and cultivate uniquely human strengths—creativity, empathy, and collaboration. It necessitates proactive businesses that invest thoughtfully in worker training and forge genuine partnerships with educational institutions. It calls for policymakers to facilitate, rather than obstruct, innovation by aligning incentives and reducing cognitive burdens on workers seeking reskilling. And it requires re-imagined labor unions and civil society to work together to enhance worker agency and dignity.

The future of work need not be a contest between man and machine. It can be a stage for rediscovering what only humans can do—if we choose to build that future together.

I think also that jobs will evolve and the talk of replacing people is currently and for some time more about replacing 'tasks'. So yes people will and have to adapt. I also did an analysis based on the historic example of electrification and industrialization and related that to current phase in AI adoption:

https://open.substack.com/pub/theafh/p/when-will-ai-actually-move-the-needle?r=42gt5&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=true

Thanks for writing this piece, and series.

Good technical point on expensing of human capital investments. I wouldn't have thought of that nuance. (Little bit smaller of a factor in ireland since corporate tax is a bit lower).

When considering how policy might help workers, I too come back to training... but I then struggle to articulate specific training programs that would be effective and robust - and so I also land at some kind of individual-tied tax-advantaged savings account (e.g. France, Singapore). It seems unsatisfactory though if the audience wants more than a free market type solution. Probably I need to read about historical approaches that worked well.

Re unions, I'm not sure whether to think they will or should become more collaborative or adversarial. I don't understand their incentives enough. The coverage in your 5 ways blog was helpful, and so will - I imagine - reading more of your blog.