From Mistakes to Misinterpretations: Casting Doubt on the Credibility of the DC Delivery Study

Three key research errors undermine the validity of the DC instant delivery study: Methodological errors, misleading presentation of results, and recommendations not supported by the evidence reported

Recently, I’ve been thinking about how there seems to be a rise in the ‘distrust’ of research. To some extent, this is likely part of the broader waves we’re experiencing today with public distrust of experts and higher education institutions. As an economist and researcher myself, I find this disheartening. But I came across a recent study that I believe may highlight why research often (though sometimes justifiably) gets a bad rap.

Last year, Georgetown University published a study by geographer Dr. Katie Wells on “The Instant Delivery Workplace in D.C.,” with Dr. Wells interviewing 41 delivery workers about their experiences working with on-demand delivery platforms such as DoorDash, UberEats, and Instacart. Since the gig economy is my area of expertise, I read the study with great interest.

I was surprised. I understand that Dr. Wells is a geographer, and perhaps in her field of study the methodology she used is deemed to be acceptable. But in the social sciences, the methodology she used (and especially how the results were drawn from the evidence presented) would not be considered as properly conducted research and would be in violation of our research norms.

This is nothing against Dr. Wells herself, as I’m sure she is following the standards set in her field of study (in geography). I’d like to use her study as an example to set the record straight for what is considered as acceptable research in the social sciences and the standards for how we draw conclusions from our findings.

Here are the key issues that cast doubt on the validity of the report:

Methodology undermines the credibility of the findings: This is a study based on 41 delivery drivers in D.C. using convenience sampling, and is therefore considered an unrepresentative sample. That means the findings cannot be generalizable and are biased (this is a technical term used in research, not a term to describe the opinions of the researcher). Dr. Wells openly acknowledges this fundamental issue in the report (pg. 20).

Based on the methodology she used, here is an acceptable way to present her findings: “A handful of DC delivery drivers have experienced these issues at select restaurants in Georgetown. More research is needed to gain a comprehensive understanding of the underlying phenomena and whether the experiences of these select drivers are representative of all DC drivers.”

Misleading presentation of the findings does not adhere to ethical research standards: Researchers must provide comparisons and contextual evidence of their findings. The report omitted key statistics as comparisons and context, which (intentionally or unintentionally) misleads readers.

The recommendations drawn are not supported by the evidence presented in the study: The recommendation that D.C. should reclassify app-based delivery workers as employees is not supported by the evidence in the study. The study’s own evidence paints a picture of instant delivery workers who are supplemental earners– who have jobs elsewhere and spend very little time on the app–and who seem to prefer these jobs as merely side gigs. I found no evidence in the study indicative of an employment relationship or that workers wanted these side gigs to be their full-time employment jobs. The recommendation to reclassify app-based contract work as W-2 employment may be motivated not by the evidence in the researcher’s report, but by the researcher’s own personal beliefs.

The Methodology is Flawed: Small Sample Size, Sampling Bias, and Findings Are Not Generalizable

If I attended a Trump rally in Iowa with thousands of people and surveyed 41 Americans on how well Biden is doing with the economy, I would not be able to conclude from this survey that most Americans believe Biden is doing a bad job. That’s because my sample would be biased.

“Biased” is a technical term in this case, and it means that I did not use a representative sample of the entire U.S. population. Therefore, we cannot use any part of the findings to generalize about the broader population of Americans. The most that we could conclude from that survey is that a handful of Trump supporters who attended a rally in Iowa do not like Biden. That’s it. We cannot use those survey results to draw conclusions about how well Biden is doing or whether Iowans like him, or whether Biden will win the Iowa elections, or even to provide policy recommendations for Biden based on what the interviewees discussed.

The DC delivery study commits many of these research errors, meaning that the results are biased (a technical term) and not representative of delivery drivers in D.C. Because of this, we cannot use those findings to draw any credible conclusions about delivery drivers in D.C.

While there are several rules to follow in order to obtain representative and unbiased results, these are at least two necessary conditions:.

Appropriate sample size: Researchers must use an appropriate sample size based on the population that they’re targeting. Sometimes survey experts give a (very) rough general rule of thumb: a sample size of at least 1,000 respondents is necessary (though not always sufficient) to produce reliable results within some margin of error.

Randomized selection method: To produce unbiased results, researchers must randomly sample the respondents. That means if my target population is D.C. residents, I cannot show-up to one neighborhood in D.C. and interview individuals I see in front of the restaurants that I visit in that neighborhood. To produce unbiased results that are generalizable, a researcher would need to randomly select the residents who are invited to be interviewed which should occur across the entire D.C. area).

The D.C. Delivery Study Uses A Sample Size That Is Too Small:

41 delivery drivers is much too small to yield any representative results–even to be considered as a “preliminary result.” There are roughly 15,000 - 25,000 platform delivery drivers in D.C. alone. A sample size of 41 is nowhere close to the required sample size needed to provide representative and unbiased results. I even scanned through several of the most prominent texts on fieldwork and survey research methodologies–across all of them, I did not see anything less than 100 respondents as the “bare bones minimum” to even discuss any preliminary results (though still not enough to be considered credible and reliable).

I emphasize again, these numbers are just guidelines, but real survey research would have to adhere to a thoughtful process for selecting the right sample size. The DC study does not do that. This is not just a “small mistake,” but it compromises the validity of the entire study. See, for example, some of the key texts in social science research highlighting how the sample size alone can undermine the entire study:

“A common mistake in survey research is selecting a sample size based on convenience or what seems feasible without statistical justification. Such practices can compromise the representativeness and reliability of the survey results.” - (Fink, A. (2003). The Survey Handbook. SAGE Publications., p. 43).

“The selection of sample size must be based on careful consideration of the research objectives and statistical principles. Relying on what seems manageable or what other studies have used without proper justification can undermine the credibility of the research.” - (Bryman, A. (2012). Social Research Methods. Oxford University Press., p. 187)

“A critical aspect of survey design is determining the appropriate sample size. This decision should be based on statistical reasoning rather than convenience or arbitrary standards. Inadequate sample sizes can lead to significant biases and inaccurate conclusions.” - (Thompson, S. K. (2012). Sampling. Wiley., p. 89)

Therefore, from the sample size of 41 drivers alone, we cannot draw any conclusions about DC delivery drivers.

The D.C. Delivery Study Uses A Biased Sample Selection Method:

The interviewers went to a handful of D.C. restaurants in only one neighborhood of D.C. (Georgetown) and solicited interviews from delivery drivers. This is called “convenience sampling,” meaning you survey the people and the area that is easiest to reach. This also means that your results cannot be considered as representative of the population, with this report explicitly stating on page 20: “There is insufficient evidence to assess whether the workers who participated in this study are representative of all instant delivery workers everywhere or even those in the D.C. area.” This admitted bias in the research is later ignored when the authors draw improper conclusions from the interviews and propose recommendations that are not grounded in the results of the study.

There are many reasons why convenience sampling in this DC delivery study does not provide representative or generalizable results, For example:

Self-selection bias: The sample over represents individuals who are most interested in expressing their opinions (likely their negative experiences in this case). As a result, you can get a sample that is mostly negative about their experiences, but you don’t know whether this is true of the broader population (all delivery drivers in DC).

Lacks external validity: If your aim is to understand delivery drivers in Georgetown, then it’s okay to survey only delivery drivers in Georgetown. However, if you want to understand delivery drivers in all of Washington D.C., you cannot choose only one neighborhood (Georgetown) to carry out the study because Georgetown D.C. is not representative of the entire population of D.C. drivers. Indeed, Georgetown is affluent and a pseudo ‘college town’--it is not very comparable to most other parts of D.C.

Over/under representation of deliverers, customers, and restaurant characteristics: It appears that not only were deliverers chosen based on convenience sampling, but so were the restaurants. This means that the study is (unintentionally) filtering specific characteristics that may not be representative of the full population. For example, the study documented that a certain percentage of restaurants would not allow delivery drivers to use their bathrooms. However, it could be that restaurants in Georgetown tend to be more “posh,” and therefore were less likely to allow delivery drivers to use their bathrooms. We cannot generalize from the Georgetown bathroom experience onto the entirety of the DC area. It is also quite possible that the bathroom experience may be worse if we sampled all of the DC area, but we have no way of knowing this unless we properly sample DC.

In summary: the findings in this study cannot reliably be used for understanding D.C delivery drivers (which the report itself admits to, but yet still attempts to generalize to the broader population).

Misleading Presentation of the Results Does Not Adhere to Ethical Research Standards

“There are three kinds of lies: Lies, Damned Lies, and Statistics” (attributed to Mark Twain)

Putting aside the methodology, there is a misleading presentation of the results. First, as discussed above, none of the findings should be discussed as representative of DC delivery drivers. That means we cannot draw any conclusions from the results of the study about DC delivery drivers as a whole.

The only appropriate way to present the results based on the methodology used is as follows:

Here are a handful of DC delivery drivers who experienced these issues at select restaurants in Georgetown. More research is needed to gain a comprehensive understanding of the underlying phenomena and whether the experiences of these select drivers are representative of all DC drivers.

Second, I found it surprising that the findings are not put into context. Generally in academic research, scholars have an ethical obligation to provide comparisons and contextual evidence. For example, if I said “50 percent of self-employed workers in our sample are insured,” this should be followed with, “which is below the national rate for workers at 70 percent.” That allows readers to understand whether the 50 percent is higher or lower than the norm.

By omitting the context of the results, researchers can unintentionally (or intentionally) mislead readers. To underscore the importance of this, imagine if I did a study of XYZ hospital and reported that 40 percent of workers at XYZ hospital faced an injury or illness on the job. This is a “clickbait” statistic that might incite a frenzy of negative reactions, severely tarnishing the hospital’s reputation. But what if the national comparison is that 60 percent of workers at all hospitals face an injury or illness on the job? That means XYZ hospital itself is doing better than most other hospitals. That is why as a researcher, I have an ethical obligation to put the number in context so that readers are not misled by the findings.

The D.C. delivery drivers study omits comparisons and the context in all of their presentation of the findings. For example:

51% of workers felt unsafe on the job.

41% of workers experienced assaults or harassment on the job.

51% of workers faced problems with bathroom access on the job.

23% of workers were in traffic collisions on the job.

While it’s always worrisome that workers may not feel safe on the job or experience traffic collisions, I’d have no way of knowing whether 51% (safety) or 23% (traffic collisions) are excessively low or high when compared to workers in the same occupation or industry. If most workers in the broader transportation and delivery industry experience unsafe conditions and traffic collisions, then the instant delivery industry is on par with the whole industry and that might mean the real problem is with the job itself (e.g. driving/biking) rather than something specifically about on-demand delivery.

But what if the safety and traffic collisions are FAR worse in the broader transportation industry? Then the instant delivery industry seems like a much better alternative for workers in terms of safety and traffic collisions.

Again, without comparisons and context, we have no way of knowing whether the instant delivery industry *in particular* is the problem or if it has something to do with the industry or job itself, just like the example I gave above with XYZ hospital.

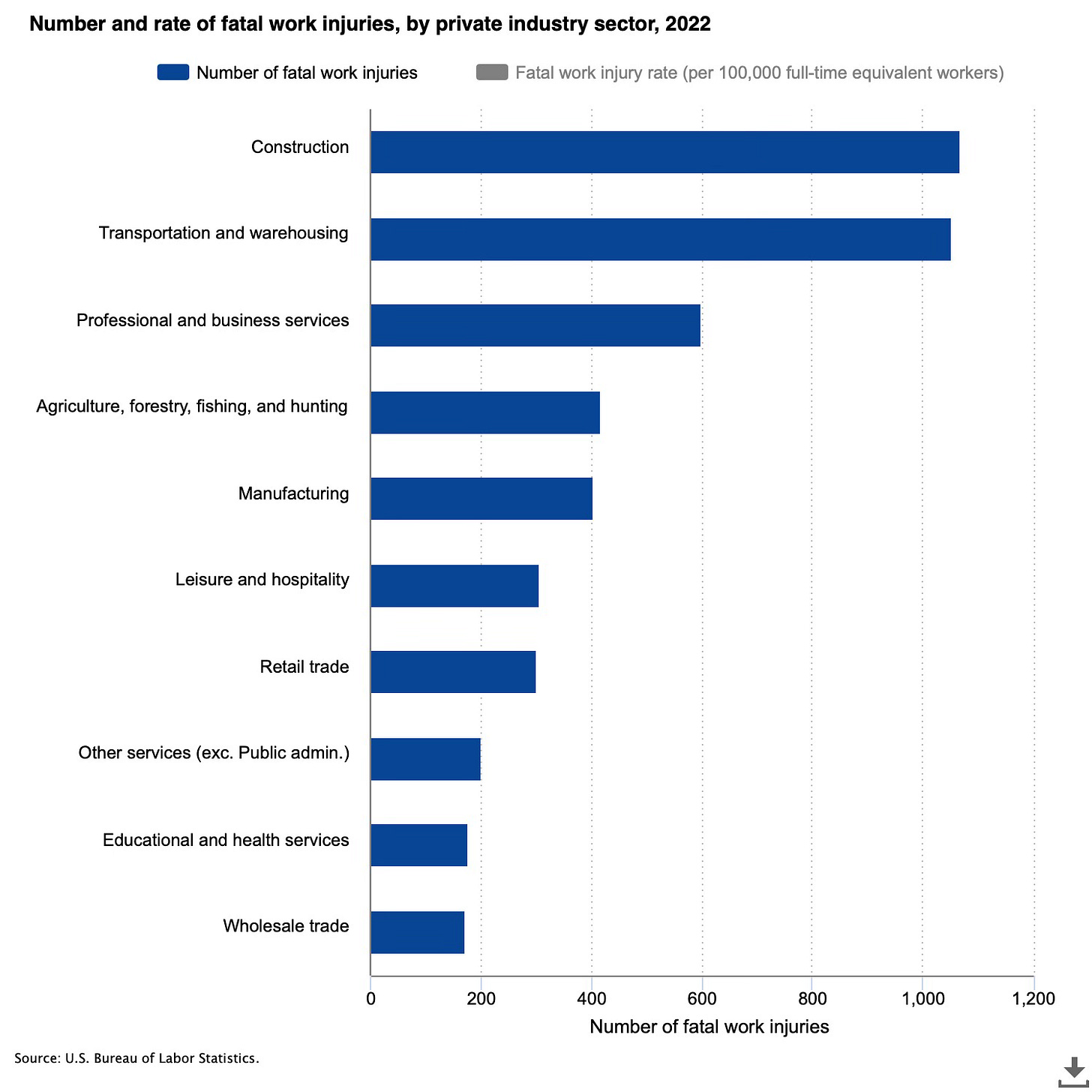

Because the context was (intentionally or unintentionally) omitted from the study, I decided to look for it myself. Below are some graphs that provide a rough approximation of “safety” from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (e.g. number of fatal and nonfatal work injuries).

After construction, transportation has the highest rate of fatal work injuries. It also ranks in the top 5 for highest rate of nonfatal work injuries. As it turns out, jobs in the transportation industry in particular are considered “unsafe jobs.” That does not mean it’s okay for delivery drivers to feel unsafe, but it means the problem likely rests with the job itself rather than with the particular sub-industry of instant delivery drivers. Given that being on the road is dangerous, driving/biking *itself* is considered a dangerous job.

Notice also how health care and social assistance workers top the charts for nonfatal work injuries and illnesses. That means if a researcher tried to present a specific hospital or sub industry without the context, that researcher, too, would be misleading you with their statistics.

The fact that Dr. Well’s study used misleading statistics does not mean that we should ignore the problems within the instant delivery industry. Rather, it means that we should focus our efforts on understanding exactly where these problems are stemming from and find productive ways to address them (e.g. how can we make changes that would enhance safety for all delivery and transportation workers).

In summary: Statistics need context. That’s an ethical standard for researchers.

Recommendation on Employment Status Does Not Align With The Evidence Presented in the Study

Let’s put aside all of the issues I’ve raised thus far which cast doubt on the validity of the report. Instead, let’s check whether the recommendations are supported by the study’s own evidence.

Take for example Dr. Wells’ recommendation that D.C. should reclassify app-based delivery workers as employees (pg. 18).

If you saw this recommendation in the report, what kind of evidence would you expect to support this conclusion? I might want evidence that workers are “treated like employees” (e.g. being required to work at specific times of the day, having a “boss” to report to, etc.), or maybe that the majority of workers are using the app as their only and full-time job ( making them “economically dependent” on the company), or that they want to be reclassified as employees (perhaps because they’re looking for full-time employment or need health insurance or other employee-related benefits).

Instead, the report does not provide evidence for any of those claims. Oddly enough, the evidence presented seems to indicate that workers should continue to have their side gigs treated as merely side gigs. Take a look at some of this evidence presented in the study:

Majority of workers are supplemental earners on the app

60% of participants had sources of income other than delivery work (pg. 15: “40% of participants earn income only through delivery work.”).

Vast majority of workers had health insurance

85% of participants had health insurance (pg. 7: “roughly 15% of workers, nearly all of whom work full-time for delivery companies, report that they do not have health insurance”). That is, only 6 people interviewed did not have health insurance.

Testimonials indicate workers treat this job as a side gig and prefer it as such (pg. 13):

Chris: “For an extra-income job, it’s not bad. I would recommend it.”

Michelle: “It’s a great way to supplement your income with a great degree of flexibility…. [It’s] a flexible way of making ends meet because, otherwise, it’s hard to find a part-time job that is willing to work with your unique life, your unique schedule, and everything else.”

Manuel: “It’s a good option as a part-time job.”

Sidney: “It’s a great second job. You can work whenever you want... When I’m on vacation, I don’t have to worry about it…. I know that if I had to do this full-time, I would be miserable. It’s great as a part-time job.

This evidence paints a picture of instant delivery workers who are supplemental earners– who have jobs elsewhere and spend very little time on the app–and who seem to prefer these jobs as merely side gigs. I found no evidence in the study indicative of an employment relationship or that workers wanted these side gigs to be their full-time employment jobs.

Now, let’s take this in combination with some other evidence in the report regarding problems with bathroom access at restaurants, waiting for orders (unpaid time), ‘tip-baiting’ practices, and under payments.

Lack of access to bathrooms is not evidence that D.C. needs to change its worker classification policies. These are two fundamentally different issues. If there are indeed problems with bathroom access, this could be resolved with Dr. Wells’ other recommendation: “Establish access to bathrooms at restaurants and retail stores where instant food delivery workers pick-up orders, and explore investment in public bathrooms” (pg. 17).

Second, the frustration that workers face with waiting for orders (unpaid time) is completely understandable. However, this is the reality for all self-employed workers, and is not a specific problem with instant delivery platforms. If you’re a self-employed nail technician and your client cancels on you at the last minute, you have an hour of unpaid waiting time until your next client arrives. That’s not evidence that the nail technician should be an employee. That’s evidence of a real challenge in this type of work, and there should be innovative ideas for how to actually help self-employed workers navigate this problem.

Lastly, any fraudulent practices like deceiving workers, or tip-baiting, or not making payments to a contractor are already illegal under existing law, regardless if the worker is an employee or a self-employed contractor. When someone accepts an offer with a specific amount, that is a legally binding contract and hiring parties are required to pay that amount. This is true for instant delivery workers, for freelance musicians, for self-employed tutors, and so forth. Such fraudulent practices are not a worker classification issue. Authorities already have the laws and the means to enforce that hiring parities abide by their legally binding offers. As needed, D.C. policymakers can pass explicit laws prohibiting tip-baiting practices.

It sum: it seems that the recommendation to reclassify app-based contract work as W-2 employment may be motivated not by the evidence, but by the researcher’s own personal beliefs.

Conclusion

We rarely have an opportunity to do a perfect study. There are limitations in all studies, and researchers have an obligation to appropriately discuss their findings. The D.C. delivery study is a fieldwork study (with only 41 interviewees) and those generally are not aimed to be representative of the population. That means the interviewees' experiences can be true and genuine, but we have no way of knowing to what extent these experiences occur, and by no means can researchers draw generalizable conclusions or “policy recommendations” from a handful of 41 interviews.

Hi, Dr. P. Thanks once again for sharing your knowledge and how freelancers are not given the choice of the question: "Do you want to be full-time?" Based on the quotes in your article, I suspect the majority of drivers would have answered no. (Note: I didn't read the original report, and I suspect doing so would cause me too much angst.) I'm a social sciences academic editor, and I agree with all of your points. Without context, statistics are just meaningless numbers followed by a percent symbol. Thank you for all you do to point out that those pushing "misclassification" on freelancers are not looking at the evidence as freelancers see it.