From the Archives: 5 Ways America Can Pursue a 'Pro-Worker' Agenda

At the heart of this challenge is that there are trade-offs in how we empower the American worker.

One year ago today, I launched this Substack. I’m so grateful to all of you for your interest in my work and for your continued support. Given the emphasis in this presidential election on ‘pro-worker’ policies, I’ve revived my post from last year, 5 ways America can pursue a pro-worker agenda, for all my new subscribers.

I was born in the Soviet Union, sometimes associated as a “worker power” paradise, where all aspects of work were regulated under the principle that every Soviet citizen must have a good, meaningful job that pays decent wages. Loosely, that meant a job was guaranteed by the government, there were rigid pay standards for each profession, it was impossible to get fired (which inevitably meant there was less job mobility), and the pursuit of income from self-employment was strictly prohibited. This latter prohibition on work is what sent my grandfather to jail for nearly a decade when he tried to earn more income by making and selling hats.

Three decades later, and several thousand miles west, I am witnessing America’s labor movement at the brink of a pivotal moment. Conservatives are now joining progressives in embracing the vital role of “pro-worker” policies (often contrasted with “pro-business” policies) for advancing the future of American society that, above all else, prioritizes worker power. Rhetoric from both the traditional left and the New Right are capitalizing on this moment. The Biden Administration’s Office of the U.S. Trade Representative just issued a proposal to investigate new regulations to pursue “worker-centered trade policy.” The conservative Heritage Foundation recently reversed some of its labor policy positions to now “reclaim the role of each American worker as the protagonist in his or her own life.”

The key question now is what policies are “pro-worker”? How is this defined? Are pro-worker policies ones that ensure job security for every worker? Or are they the policies that try to maximize job opportunities for workers? Are pro-worker labor unions ones that have greater political power or ones that can best serve employees in their respective workplaces? Do pro-worker policies also focus on workers as consumers who can access goods and services and new technologies at lower prices—thereby increasing their standards of living?

At the heart of the challenge in pursuing “pro-worker” policies is that there are trade-offs in how we empower the American worker.

Greater Job Security or More Work Opportunities?

While you may think of Italy as the land of endless beautiful landscapes, food, and art, it is not a country known for its thriving labor market. Indeed, my husband and almost all his well-educated cohort from Bocconi University, the highest-ranked economics program in Italy, were forced to seek employment abroad upon graduation. Less than ten years ago, Italy’s youth unemployment rate was at a staggering 45 percent, and even now at 25 percent, Italy’s youth unemployment rate is one of the highest in the developed world.

It is no coincidence that Italy is also known for having one of the most “pro-worker” labor policies among its Western counterparts—one that provides extensive job security and decent wages for current workers and makes it almost impossible for businesses to fire employees. But, as a result, employers are hesitant to hire workers, especially inexperienced youth, older workers, or where it’s unclear how the worker will perform on the job. There is little labor market mobility or turnover—so if you’re going to search for a job in Italy, you will have better luck finding charming cafes on the cliffside.

In fact, a set of studies found that when Italy even slightly reduced protective employment regulations, it led to increased employment and more jobs for younger workers. But Italy is not a stand-alone case. Through case studies around the world, economists have long documented how more-restrictive labor regulations, especially regarding job security, lead to less labor mobility, fewer job opportunities and higher unemployment rates.

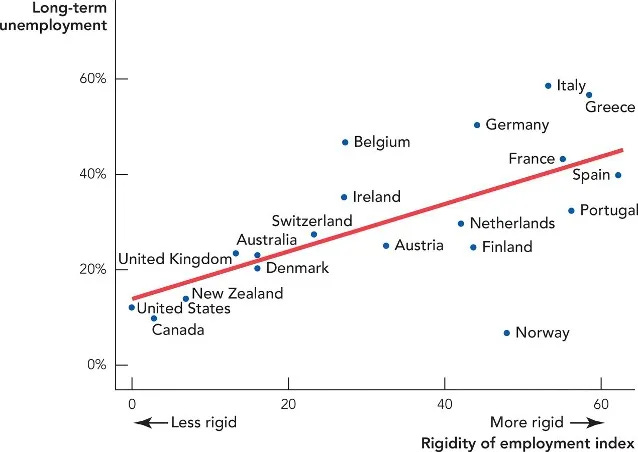

In essence, countries with more rigid labor markets tend to have much higher unemployment rates and fewer job opportunities—a trade-off that a pro-worker policy agenda must grapple with. Yes, employment protection regulations can help with job security and job stability for existing workers who are already in those positions, but it comes at the expense of harming new workers, labor market dynamism, and reducing job creation.

Ensuring Good Jobs and High Wages: But for Whom?

Small business establishments make-up the backbone of American society. Creating a small business is often the source of income for underprivileged and minority workers. While there are some small businesses that make high profits, many small business owners, especially those with fewer than five employees and typical of your town’s “Main Street” establishment, can earn an average salary of $29,000 per year. That’s far below the national average mean wage.

What that means is when organizations like the American Compass or the Economic Policy Institute call for new policies to force businesses to increase wages, they are in practice calling for a transfer from low-income small business earners to low-income wage earners.

Beyond the fact that some small business owners are also low-income earners, they are the worst low-income earners to make unemployed. Why? Because they are low-income workers that employ hundreds of thousands of other low-income workers. If they become unemployed because a regulatory change makes it too expensive for them to operate their business, all their employees become unemployed too.

Some may argue that if the small business cannot sustain decent wages for workers, then it shouldn’t exist at all. But that again illustrates a trade-off in “pro-worker” policy proposals since the small-business owner is a worker who employs many other workers and, like those other workers, aims to make a living and sustain their family.

For example, existing rhetoric on the minimum wage points to the “big corporations” that can afford the minimum wage hikes (a “pro-worker” policy), but is virtually silent on the impact it would have on small business owners, many of whom are also low-income earners.

A recent study uses one of the most comprehensive tax datasets to examine the question of how the minimum wage impacts the owners of businesses who pay the minimum wage. The study, conducted in Israel, found that while minimum wage hikes reduced profits of companies (with minimum-wage intensive companies bearing the bulk of the cost and adjusting their workforces more aggressively), the profits declined more for lower-income business owners. Indeed, owners of businesses with higher shares of minimum-wage workers ranked at the bottom of the income distribution of business owners.

Again, this highlights the trade-offs in the current proposals for “pro-worker” policies from both the right and left. A rural household where the main income earner is a barber at his own shop and employs three others perhaps should not be the collateral damage of these “pro-worker” policies—he, too, is a worker we must consider in this dimension.

A Vision for a Pro-Worker Agenda

When my family and I moved to rural America in the mid-1990s, we found it stood true to its symbol as the land of opportunity and abundance. Work was readily available, and my parents also found plenty of opportunities to pursue other sources of income through self-employment, contracting, or starting their own businesses. Within two decades, we experienced the income and intergenerational mobility that should be at the heart of every pro-worker policy agenda. My family was privileged to enter an economy with a lot of job turnover and open doors, largely because the United States was one the world’s most entrepreneurial, dynamic and flexible economies, which created a plethora of work opportunities for millions of people.

Generally, we would want a pro-worker agenda to maximize this promising aspect of American life—a flourishing and dynamic entrepreneurial environment that constantly creates better jobs, destroys worse ones, and allows for greater labor market mobility. At the same time, a pro-worker policy agenda should create better infrastructure to support workers and low-income earners without hindering the beneficial aspects of a thriving and dynamic labor market. What does this support look like?

1) Promoting a vibrant entrepreneurial environment

In a recent piece, I outline how we can promote an abundance of work opportunities through a vibrant entrepreneurial environment. Unfortunately, the rate of startup entry and the pace of business and employment dynamism in the U.S. has been falling over recent decades and patterns suggest that the incentive for entrepreneurs to start new firms has diminished over time. Countless studies have documented that too much red tape for businesses impedes economic activity, startup entry, entrepreneurship and job creation. This is especially true for early-stage entrepreneurs who are often resource- and cash-constrained. Indeed, one recent analysis of U.S. regulations across industries finds that greater industry regulations are associated with lower firm startup rates and fewer new hires, especially among smaller businesses.

Generating an abundance of work opportunities begins with creating a welcoming environment for existing businesses and for new entrepreneurs to build, scale and hire workers. For that process to unfold, we need to ease the regulatory shackles and revive our once vibrant and dynamic entrepreneurial environment.

2) Welcoming new and diverse forms of income-generating opportunities

Each one of us can provide a job for other members of our society when we hire a music teacher or a tutor, when we order customized T-shirts on Etsy, when we request a ride from the airport, or when we have an electrician inspect our homes. We should toss-out outdated notions that jobs can only be provided by established companies.

There are more than 60 million workers earning income—either as a primary or secondary source—through these nontraditional means. The main beneficiaries of this type of work are those who place the greatest premium on flexibility—often these are women who are primary caregivers or workers with other personal circumstances that prevent them from working in traditional employment. While some aspects of this type of work are not ideal, prohibiting non-traditional work arrangements will surely reduce income opportunities for workers.

3) Redesigning labor unions to be an effective voice for all workers

In my piece for Newsweek on Labor Day, I outline how redesigning rules around organized labor can unlock the future of an innovative and worker-centric labor movement. The most important avenue is to reform the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) of 1935 to promote a more diverse union landscape in which workers can choose the one that best serves them. Currently, the NLRA prohibits any formal cooperation between workers and the employer that is outside of the government-granted monopoly union, thereby banning other mechanisms to enhance a worker’s voice.

In an extensive and high-profile study entitled What Workers Want,economist Richard Freeman and law professor Joel Rogers concluded that our current system had not delivered to American workers the diverse set of institutions they sought in the workplace. Instead, it offered a single choice—collective bargaining through the winner-takes-all union—or no independent representation or participation in the workplace. To meet the wishes of the American workforce and enhance workers options, the NRLA must be reformed to encourage a more cooperative, competitive, and diverse environment for worker representation.

4) Reducing regulations and rigidities in the labor market

As discussed above, several types of labor market regulations are counterproductive for a pro-worker agenda. Reducing these rigidities would help lower long-term unemployment, increase labor market mobility, and expand job opportunities for workers. In a forthcoming piece, I will unpack these regulations and how they impact our labor markets.

5) Pursuing more constructive safety-net policies to address low wages and poverty while creating fewer labor market distortions

For several decades, countless economists and scholars have argued for safety-net policies that are free from the type of labor market distortions discussed in this piece. This means, for example, that instead of calling for increasing the minimum wage, there should be more policy solutions such as reforms to the earned-income tax credits to better address low wages and poverty. The key insight from these researchers is ensuring an effective safety-net that protects and empowers workers without constraining and impeding on our labor markets.

America does indeed need a new labor movement—but we need one that generates a thriving labor market with an abundance of work opportunities, while at the same time offering reasonable safety-net measures that do not impede the beneficial aspects of our labor markets and the future economy. Our path forward should rebuild resilience in our labor markets to technological, cultural, or global adaptations and one that benefits all types of workers, businesses, and the broader economy.