From the Rust Belt to the Ports: A Warning About Extortive Union Demands

Not all labor unions are ‘pro-worker.’ With 36 ports striking today, the International Longshoremen Association is threatening other jobs, “I will cripple you, and you have no idea what that means."

In general, labor unions are meant to be a force for good, providing a much-needed voice and representation for workers in negotiations with their employers. However, challenges arise when bargaining demands become unreasonable or unfair–perhaps the demands from the labor union are too high or the company’s offer is unreasonably low.

Labor unions can turn into “villains” when their demands become excessive and extortive.

This is why the International Longshoremen Association (ILA), the only labor union controlling all ports across the entirety of the east coast, is facing a public backlash for demanding “a total ban on the automation of cranes, gates and container movements that are used in the loading or loading of freight at 36 US ports.” This demand is in addition to other requests on compensation – for example, significantly higher wages and benefits packages.

As many have pointed out, companies have already agreed to offer reasonably higher compensation packages to port workers–increasing wages by nearly 50%, tripling employer contributions to employee retirement plans, strengthening health care options, and even retaining the current language around automation and semi-automation.

However, in order to force companies to meet their unreasonable demands on the use of technology and even higher compensation packages, the ILA is threatening the country by locking down 36 ports on the east coast with more than 45,000 workers on strike starting today. Economists have already discussed the severe negative effects consequences this will have on supply chains, prices, and even jobs for Americans in other sectors. But perhaps the best illustration of how American workers will be worse off during these port strikes comes from the ILA union President:

“When my men hit the streets from Maine to Texas, every single port locked down. You know what's going to happen? I'll tell you. First week, be all over the news every night, boom, boom, second week. Guys who sell cars can't sell cars, because the cars ain't coming in off the ships. They get laid off. Third week, malls are closing down. They can't get the goods from China. They can't sell clothes. They can't do this. Everything in the United States comes on a ship. They go out of business. Construction workers get laid off because the materials aren't coming in. The steel's not coming in. The lumber's not coming in. They lose their job.”

This interview highlights the trade-offs that any pro-worker agenda must grapple with (as I’ve discussed in a previous post). When the ILA threatens to cripple other jobs in the economy, it is illustrating that not all labor unions are synonymous with being ‘pro-worker.’ Indeed, the ILA is okay with other workers in America losing their jobs in order to pay for the excessive demands of this select group of workers. This is hardly an inspiring message to join the American labor movement.

Of course, companies are right to reject the excessive demands, especially on a *total* ban of automation. Making U.S. ports worse-off is not a winning strategy for workers, and especially not for U.S. port workers.

If there is a total ban on automation, cargos will be redirected to more efficient and lower cost ports as east coast ports become less efficient and more costly compared to other ports that welcome technological advancements. Over time, the 36 east coast ports that are stuck in the Stone Age will see less business, slower employment growth, more lay-offs, and some may even close down completely.

Blocking technological advancements is not only bad for the East Coast ‘Stone Age’ port workers, but it’s also bad for America’s competitive edge. Asian and Middle Eastern ports which do welcome technology will continue to grow faster in the long run compared to the U.S. ports. For those who sympathize with MAGA goals, banning technological advancements on U.S. ports is a great “American Last” strategy.

For those who may seem unconvinced of this future reality, look no further than the case study of the Rust Belt’s economic deterioration in the second half of the 20th century.

A Warning to Port Workers: How Excessive Labor Union Demands Ruined the Rust Belt

A new study published in Journal of Political Economy showed that excessive demands from strong unions, which led to a high frequency of strikes in the Rust Belt region between 1950-2020, are one of the main reasons for the decline in manufacturing employment in the Rest Belt during that time period.

Rust Belt manufacturing industries had, by far, the highest rates of work stoppages from strikes in the United States. According to CPS data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, between the years 1973 and 1980, 48.1% of workers were union members in Rust Belt manufacturing compared to 28.4% among manufacturing workers in the rest of the country. As the economists note, “While unionization rates in manufacturing were around twice as high in the Rust Belt as outside, rates of work stoppages were about seven times as high in the Rust Belt. In other words, labor relations were particularly fraught among unions concentrated in the Rust Belt.”

During this time, the compensation package demands were also higher than usual as compared to the demands in other regions.

So what happened? Excessive union demands, strikes, and work stoppages led to lower average rates of investment and productivity growth by Rust Belt firms relative to those in the rest of the country. Over time, employment moved from the Rust Belt to the rest of the country.

This is common sense. Rust Belt firms faced increasing labor costs and reduced productivity, forcing many to either downsize or relocate to regions with less union influence and lower labor costs.

Overall, these labor union conflicts accounted for 55% of the decline in the Rust Belt's share of U.S. manufacturing employment, leading to its economic deterioration throughout the second half of the 20th century.

Many might sensibly ask, “but what about the impact of China and globalization on the Rust Belt?” The study accounted for this as well, finding that trade had a secondary, negative effect on the Rust Belt. As they write (pg. 2783):

Rising imports have virtually no employment effect until the mid-1970s, and the losses are concentrated in the 1980s and 1990s. This suggests that international forces at best played a supporting role in the Rust Belt’s decline in the latter part of the time period and likely had little to do with the large secular decline in the region’s employment share that occurred in the first 3 decades after the end of World War II.

The Rust Belt case study is a perfect example of when unions go too far, leading to worse worker outcomes in the long-run.

Other studies also show that unions which moderate demands to avoid pushing firms out of business or reducing employment are more likely to persist over time. This moderation creates a balance between gains for workers and ensuring the firm’s survival, benefiting both parties in the long run.

Port Automation: Yes, Some Port Jobs Will be Lost, but Fear Not

Economists generally agree that real wage growth is feasible when there are technological developments that make workers more productive, like how our generation experienced the ‘computerization’ of white collar jobs, or when the construction industry started using construction vehicles and other machines. These developments are welcomed because they enhance the skills of workers, making them more productive and allowing them to increase their output for any given hour.

Take a look at this video on how automation in Chinese ports have made port workers more productive, transforming the nature of their tasks from physically opening and closing gates to sitting behind a computer screen to direct port activity.

The concern that automation might mean certain types of jobs will be lost is real. What this typically means is that some or many of the port workers will go into completely different types of roles in the same industry (e.g. the Chinese case where they are behind the computer screen), or they will enter into other expanding industries where their skill sets are in demand.

It’s not uncommon for entire types of tasks or roles to be lost. What many neglect to understand is that technological advancements will either expand the same industries and/or create entirely new jobs that never existed before. For example, there are no more workers in the video tape industry today, but there are thousands in the streaming industry. Economists call this “creative destruction”--old jobs are destroyed, new jobs are created.

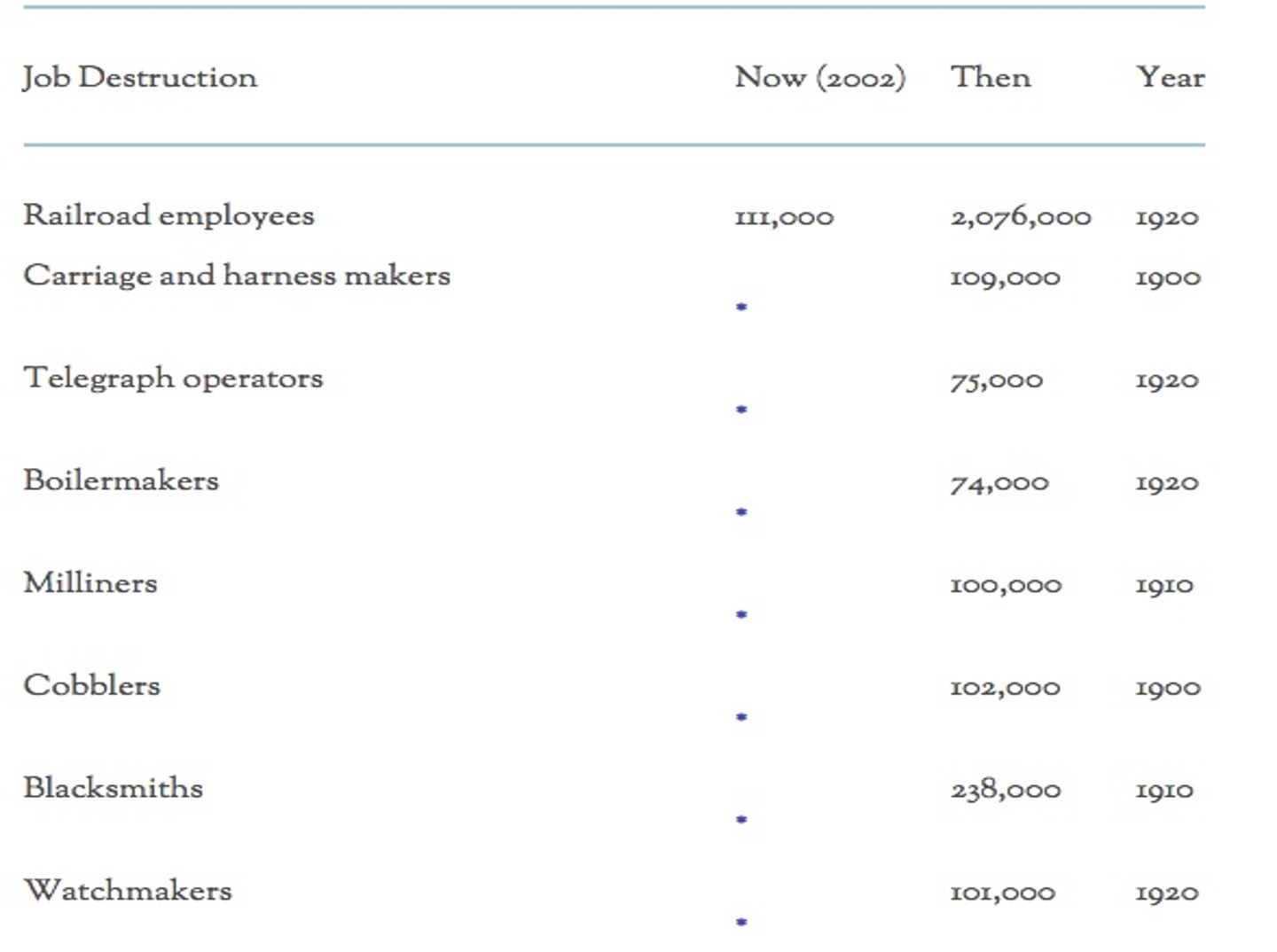

While outdated, I’ve always liked this piece on how to understand job destruction and job creation from a historical perspective. Here is a job destruction list of some jobs that have been significantly reduced or completely eliminated since the start of the 20th century.

And here is a job creation list showcasing the expansion and creation of new jobs since the 20th century (at the time of this report, the authors used jobs in 2002). Notice, for example, there were zero electricians, auto mechanics, and airplane pilots and mechanics. Today, there are hundreds of thousands of them.

While some jobs were eliminated, more jobs were created and the economy grew overall. This is all part of a healthy, dynamic process in our economy.

So yes, some port jobs in the future may be reduced, but that’s not bad for workers in the long-run. The economy expands with technological advancements, enabling the creation of new jobs and industries in the process.

Insightful, as always!

So how do you transition these workers so the automation doesn't completely crater all their jobs? How did all these other countries transition to automation while giving the current workers a "soft landing" to something else?