The Battle in Massachusetts: Are Ridesharing Drivers Employees or Independent Contractors?

Three questions: (1) Who's in Control, (2) Married or Casual Dating?, and (3) Economically Dependent? BONUS: Our recent study on whether there are 'real' differences between employees & contractors

Yesterday was the first day of a trial in Massachusetts on whether Uber and Lyft drivers should be classified as independent contractors. In March, I testified before the Massachusetts legislature on this same issue (full testimony is published here and you can watch the hearing here, my remarks begin at 0:54:55).

This is an ongoing, contentious debate across the nation regarding the work status of drivers. So, are Uber and Lyft drivers misclassified employees? Short answer: no, and here’s why:

1) Who’s in control?

Laws governing whether a worker is classified as an employee or independent contractor differ by state and even by federal agencies. However, there are a few general principles across worker classification tests that I’ll cover in this post, the most important of which is about control.

Whether a worker is considered an independent contractor or an employee is largely a matter of how much control the hiring party is exercising over the worker. Employees give up a lot freedom over how they work (including number of hours, schedule, location, how the job gets done, etc.). A properly classified independent contractor has the freedom to decide whether to work, how to work, where to work, how many hours to work (and how often to work), and so forth.

If an employee at Starbucks decides to work only an hour of her 9-5pm shift and then crosses the street to work for a local coffee shop, that employee would likely be fired. If a driver turns off his Uber app and switches over to work with Lyft, that driver will continue working with both companies.

The difference is that the legal contract between an employee and an employer stipulates that the employer has control and discretion over how the employee utilizes his or her time. Of course, the employee may still come in late, or leave early, or take a 2-hour break, but the key point here is that the employee must ask, and the decision on whether that employee can leave in the middle of the day rests with the employer.

On the other hand, hiring parties of a contractor cannot legally exercise that kind of control over the independent contractor. In cases where a company forces an independent contractor to show-up at specific hours and provides specific break times and fires the independent contractor who does not comply, that worker is likely misclassified. In those cases, the worker “looks like” an employee, but is legally classified as an independent contractor. But that is not the case in the Uber and Lyft context, where drivers have meaningful control over when to work, where to work, how often to work, and whether to work at all. In other words, Uber and Lyft drivers don’t “look like” a typical employee.

Now, the debate comes into play when we introduce other aspects of control, mostly importantly in a ridesharing context: control over setting their own rates. Uber and Lyft use an algorithm to calculate dynamic fares, so drivers do not set their own rates. But neither do taxi drivers, who are also considered independent contractors.

As I previously wrote in my Hill column, in the context of taxis and ride sharing, that’s not necessarily a bad thing. The majority of Americans don’t want to bargain shop from a rainy street corner. The time and hassle of searching for available and safe rides, and haggling over the price, defeats the purpose of an “on-demand” ride. The same is true for the other side of the market. Without instant matching, idle drivers face longer wait times and less motivation to offer services.

The other ways Uber and Lyft might exercise control over drivers are connected to background checks, vehicle requirements, and other driver safety or quality checks. But these standards help provide a safe ride, and importantly, they are often legally mandated. Standards and safety checks are also available in other contexts where the independent contractor status is more clear. Let’s say you want to hire a dog sitter, and you use a platform or agency to connect you to one. The reputation of the platform or agency is on the line if the dog sitter is a “bad apple.” So the platform may ask a dog sitter to pass a background check or provide other quality check measures. Or perhaps the platform delists dog sitters who have previously engaged in egregious conduct (e.g. harming the dogs).

Indeed, what the ridsharing and dog sitting platforms provide is some quality control matching. There is a reason you didn’t choose to look for your dog sitter or your driver on Craigs List. Presumably, you wanted some quality control.

Taken together, there are some aspects of control (mainly on price setting and safety/quality considerations) where Uber and Lyft are exercising some degree of control, but the average Uber or Lyft driver does not look like a typical employee in a meaningful way. Now, one may argue that the driver also doesn’t look like a “typical contractor,” but that’s not an argument to make the driver an employee—rather that’s an argument for a third-way category, like the status of an Uber driver in the United Kingdom (drivers are “workers” which is a middle category between “contractors” and “employees”). Many years ago, I published a law review article for the University of Chicago Legal Forum arguing that driving in the ridesharing context is a relationship not well captured by the current employee/contractor model.

2). Married or Casual Dating?

Another key factor is the degree of permanency of the relationship between the worker and the hiring party. If a worker lacks a permanent or indefinite relationship with an organization, that can be indicative of an independent contractor status.

In other words, think about the employment relationship as “getting married” while the contracting relationship is more like “casual dating.” In the marriage/employment relationship, there is an expectation of permanence—that you’re in for the long-haul until someone indicates (usually with two weeks notice), that they’d like to file for a divorce.

In the contracting case, neither party expects the relationship to be permanent or exclusive. Sometimes you’re even casually dating between two arch rivals.

For the Uber and Lyft context, this factor most certainly illustrates the independent contractor status. Drivers are not restricted or punished for working with multiple platforms at the same time or switching between platforms in any given hour. A driver can work for five minutes today, two hours tomorrow, and then never open the app for the remainder of the month. That same driver can easily log-on to the app later that year.

In the employee-employer context, there is an entire structure around hiring and firing that codifies the expectation of permanence that defines the relationship, which is absent in the contractor-employer relationship. In other words, a driver “ghosting” is actually the norm in the gig economy. Workers and companies aren’t in a long-term marriage/employment relationship, so neither party is expected to formally “marry” or “divorce.”

3). Economically Dependent?

Closely related to the second point on permanence, some worker classification tests aim to understand whether a given worker is “economically dependent” on the hiring party. Generally, if the worker has multiple sources of income or is using that job as a supplemental source of income, they are not considered economically dependent on the organization and therefore more likely to be considered an independent contractor.

In the Uber/Lyft context, the data on workers as side hustlers is unquestionable.

Let’s start with the official IRS tax records. Tax data show that app-based workers are primarily supplemental earners who have full-time jobs elsewhere. I will quote directly from the IRS report on this: “The exponential growth in the online platform economy for labor is driven by individuals whose primary annual income derives from traditional jobs and who supplement that income with platform-mediated work.”

This finding from the IRS report confirms what we see in the companies’ own data:

Lyft: 96 percent of drivers work elsewhere or are students in addition to driving

Doordash: 90 percent of “Dashers” worked less than 10 hours per week on delivery

Economist Jonathan Gruber, head of the economics department at MIT, found a similar pattern in his recent study: the vast majority of those who drove with Uber were doing it on a supplemental basis and were either full-time employees, students, or retirees.

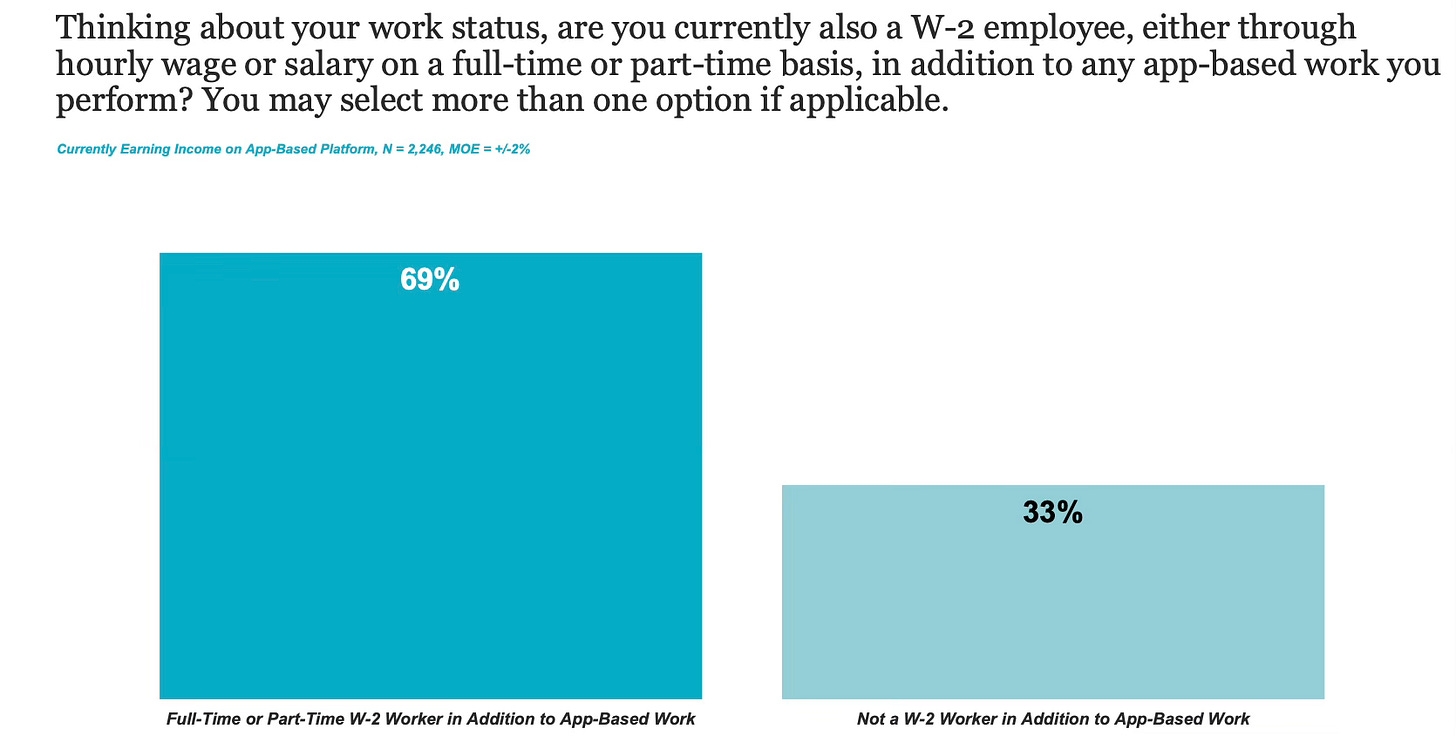

Another survey that aggregates workers from across the major app-based industries also finds that 69 percent of app-based workers already have a full-time or part-time W-2 job.

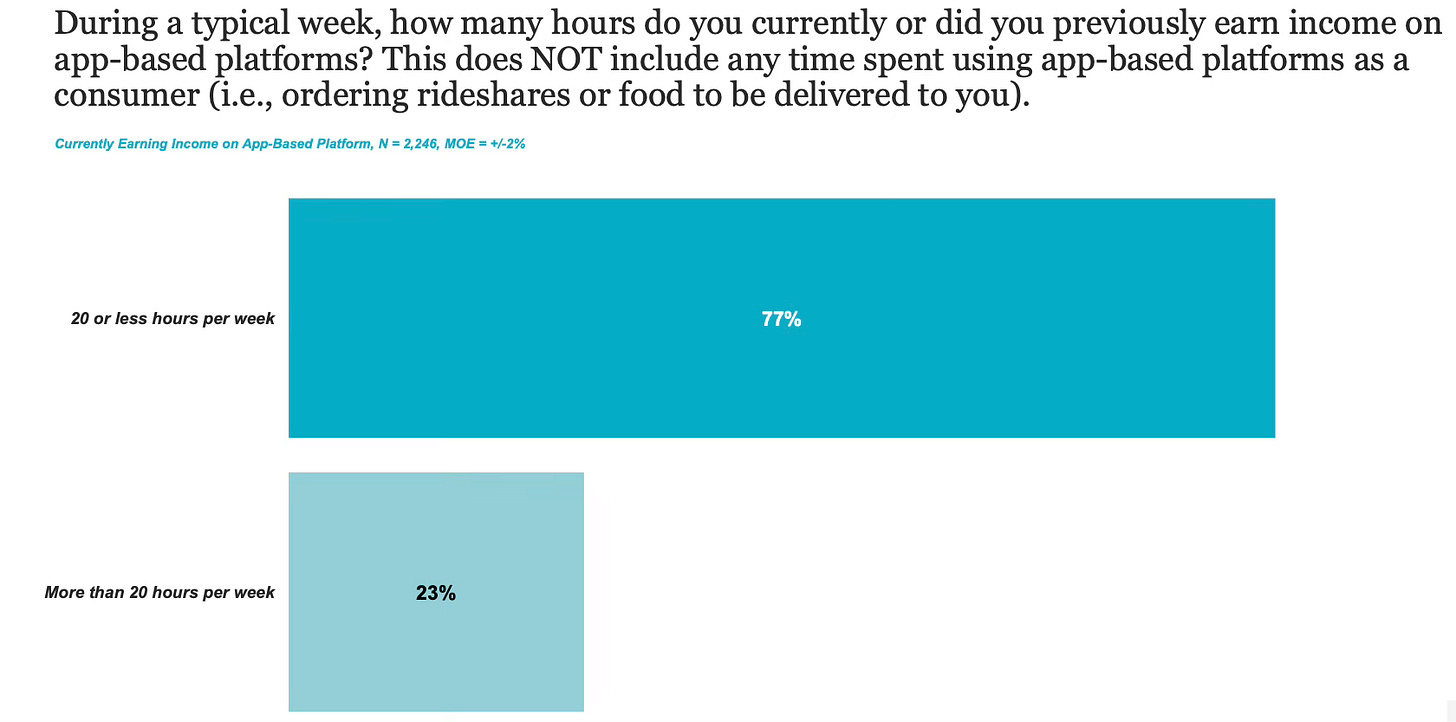

Similarly, about 77 percent of app-based workers also indicated that they work on those platforms less than 20 hours a week.

The supplemental nature of gig work is supported by every other study I’ve seen on this question, regardless of the data used or the organization that conducted the research.

Key takeaway: The majority of drivers are not “economically dependent” on Uber/Lyft, therefore, they look more like independent contractors than employees under this consideration.

4). What about the other factors?

The three considerations I’ve outlined here are not meant to be exhaustive. There are several factors I didn’t discuss (e.g. relative investment, skills, integrality, etc.). Rather, I am providing the general framework for thinking about the worker classification tests under these broader considerations of control, permanence, and economic dependence.

However, I will mention one more consideration, which is rather controversial, called “integrality,”—it asks whether the work performed is an integral part of the employer’s business. If the work performed is integral to the employer’s business, this is a ‘checkmark’ for the employee side. In my opinion, this is not a helpful consideration for determining whether a worker is truly an independent contractor or not.

Here’s why: If a music venue is hiring a freelance musician for a gig, that means the musician’s work (“the music performed”) is an integral part of the employer’s business (a music venue), therefore it would be difficult to hire the musician as an independent contractor. But the nature of the relationship between the musician and music venue could be, without a doubt, indicative of the contractor/freelancer status. Yet if the law props up the integrality factor, a true freelance musician may have to be reclassified as an employee since the music performed is an integral part of the music venue’s business. This would kill entire industries of properly classified independent contractors (e.g. writers and magazines, tutors and educational organizations). This is why when California passed Assembly Bill 5 (AB5), the musicians fought tooth and nail to be exempt from the law because performing a musical “gig” for a music venue is at the foundation of their industry.

In the ridesharing context, the integrality factor is a question of whether Uber and Lyft are technology companies or transportation companies—if the latter, then “driving” would be considered an integral part of the company’s core business.

BONUS: Our research on REAL work differences between contractors and employees

Beyond the legal question, my co-author Paola Suarez and I were interested in understanding whether there are inherent ‘nature of work’ differences between workers who tend to be classified as independent contractors or as employees. We published a study on this—short answer: there are real ‘work differences’ between independent contractors and employees.

We analyzed over 900 occupations and specific characteristics from the Department of Labor’s O*Net database and found that independent contractors are entirely unique in the type of work they produce when compared to traditional employees.

Contributions from typical employees are interdependent with teams and have greater elements of interactive coordination, communication, and shared responsibilities and results. Independent workers, in contrast, tend to provide an individual-based product or service that’s more easily separable and discrete—like creating a screenplay, tutoring a student, or giving someone a ride to the airport.

The above figure is from our study, and it shows a simple average of the work characteristics across some common examples of independent work occupations (in orange) and nonindependent work occupations (in blue).

As shown, occupations such as taxi drivers, couriers, and messengers are well below the independent work group average—meaning that these are occupations that have much less reliance on team production and coordination and have greater separability of individual outputs relative to nonindependent work occupations. If we compare the extremes, education administrators (almost always classified as employees) score almost twice as high as taxi drivers and chauffeurs in our independent work index.

What does this all mean for the debate? There are fundamental differences in the nature of work between independent contractors and traditional employees, which appropriately justify why we see legal differences in worker classification between the two types of jobs, though they do not imply that the worker classification categories should be binary. Some policies (like California’s AB5 for example) thereby overlook the diversity of work characteristics between independent work and employee jobs by attempting to fit both sets of jobs into the same legal worker classification, even when they exhibit intrinsic differences.

Agreed on most points, but a side note:

Ridesharing apps offer marginal incentives (discounted insurance, deals on vehicles and maintenance, and other deals) that are attainable only by a subset of the 23% working over 20 hrs/wk. It's a brilliant and devious mechanism that are basically employer perks without being called as such. I'm no judge, but I wonder if that enters the legal argument at all.

Thank you for always making the economic point that freelancers are not misclassified by default. We know that we are freelancers, even if certain state governments, the federal government, and federal agencies currently act as if we are too naive (or stupid) to know the difference between W2 and 1099 work.