The Future of Flexible Work is Female

What Claudia Goldin’s Nobel Prize in Economics Means for Women in the Workplace

This month the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for 2023 was awarded to economist Claudia Goldin for her comprehensive account of women’s labor force participation and earnings through the 20th century and for uncovering the key drivers of gender differences in the labor market. Goldin is the first woman to receive a solo Nobel Prize in economics, and the third woman overall to receive the prize. The first female recipient was political scientist Elinor Ostrom in 2009 for her work on governing the commons, and the second was Ester Duflo in 2019 for her experimental approach in development economics. Goldin was also the first woman to receive tenure in Harvard University’s economics department in 1989.

In this post, I focus on Goldin’s contributions on flexible job arrangements and what it can mean for women in the workplace today.

Among her contributions, Goldin’s research showed how oral contraceptives impacted women’s educational choices and careers, and she also highlighted a U-shaped curve for female participation in the labor market: as economies transitioned from agriculture to industry, female participation fell—but it rose again when we transitioned to a service economy.

Goldin is most well-known for her work that uncovers the causes of the gender wage gap: she found that the gap takes off after the birth of a woman's first child and the career choices she makes as a result of jumpstarting on the path of motherhood.

For example, in one research study, Goldin and her co-authors follow the career paths of male and female MBA graduates in an elite program from 1990-2006. At the start of their careers, male and female graduates have almost identical labor incomes, but their earnings begin to diverge 5 years after graduation and this earnings gap continues to widen 10-16 years after the MBA completion. If they start-off on identical paths, why do female MBAs later perform worse than their male counterparts?

Goldin and her co-authors find that the large growth in the gender gap in earnings is a consequence of gender differences in career interruptions and weekly hours worked—which are largely associated with motherhood. Any career interruption (of 6 months or more out of work) is costly in terms of future earnings for these high-paying jobs. Women with children also typically work 24 percent fewer weekly hours than the average male; while women without children work only 3.3 percent fewer hours.

They conclude that the careers of MBA mothers slow down substantially within a few years following their first birth. MBA mothers are actively choosing jobs that are family friendly and avoiding jobs with longer hours and greater career advancement possibilities, which contributes to the divergence we see in male and female labor market outcomes.

Overall, Goldin’s work showed that historically the gender wage gap has been attributable to the distinct educational and career choices that women make. She argues that the remaining gap today can be closed if jobs become more flexible.

The Price Women Pay for the Work Flexibility Amenity

“A flexible schedule often comes at a high price, particularly in the corporate, financial, and legal world”

“The gender gap in pay would be considerably reduced and might even vanish if firms did not have an incentive to disproportionately reward individuals who worked long hours and who worked particular hours. Such change has already occurred in various sectors, but not in enough”

-Claudia Goldin, A Grand Gender Convergence, 2014

Flexible job arrangements can be transformative for working mothers, but in some types of industries and occupations, flexibility can come at a high price. In her American Economic Review article, “A Grand Gender Convergence,” Goldin argues that the remaining gender wage gap (after accounting for differences in education, full-time vs part-time employment, and occupational choices) is attributable to jobs that are less flexible—e.g. jobs that demand long hours, specific work hours, being on-call, or being available for face-time, especially for clients.

There are certain occupations that impose high penalties on employees who want to work fewer hours and who want to have more flexible job arrangements. This can lead the employee to shift to an entirely different occupation, to a different position within the occupational hierarchy, or to leave the labor force altogether.

Goldin offers an illustrative example: partners at a large corporate law firm pay a premium for working long and continuous hours, and they are often required to be physically present for face-to-face discussions with colleagues and supervisors, attend group meetings at specific times, and to always be ready for immediate and time-pressing meetings with clients. A female lawyer with kids may decide instead to work at a smaller law firm or as a general counsel at a company, where she can work fewer and more flexible hours, but is also paid significantly less than she would have made at the large corporate law firm.

In other occupations and sectors, such as in technology, Goldin finds these jobs appear to enable women to work part-time or to work more flexibility without a large “pay penalty.”

This focus on flexibility for women comes at a pivotal moment in our labor markets as flexible job arrangements are taking-off post-pandemic along with non-traditional work arrangements, such as freelancing and platform-mediated work.

The Future of Flexible Work is Female

One positive outcome post-pandemic was a greater acceptance and move toward remote working and other types of flexible work arrangements. Some companies even issued forever “work from home” policies. These structural changes in traditional employment arrangements are a beneficial change for working mothers.

At the same time, we are witnessing a growth in non-traditional work arrangements (such as in freelancing, platform-mediated work, or other independent work opportunities), where flexibility is a staple feature of that work. According to official IRS tax data, since 2001, the participation in this type of independent work is growing significantly more among women than men. In fact, the tax data also indicate that female independent contractors are more likely to have children than female employees. And, a 2023 survey highlighted the growing share of women switching from traditional full-time employment to independent work opportunities, mainly because they prefer to work from home and want more flexibility in their schedules.

That should come at no surprise: remote and flexible work is making it easier for moms to juggle both parenting and their careers.

How important are these independent and flexible work arrangements for mothers? A recent study analyzing panel data from the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) and American Time Use Surveys shows that self-employment rates are higher for women who have young children and that self-employed female workers seem to have more flexibility in their work location, hours, and schedule as compared to women in traditional employment.

Mothers with young children at home use self-employment opportunities to spend an additional two hours per day with their children. The study concludes that overall, these non-traditional work opportunities give mothers “more control over their work environment allowing them to better manage their household while working.”

In a survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation (in partnership with CBS and the New York Times), researchers found that about 75 percent of self-identified homemakers, or stay-at-home mothers, in the United States indicated that they would likely return to work if they had flexible options.

Given this preference for flexibility, it is also not surprising that women are seeking out the growing number of independent work opportunities that are on the rise today. Some women seem to be working on gig platforms such as UberEats and DoorDash, while others are setting up online shops with Etsy (year after year, greater than 85 percent of Etsy shop owners are women), or engaging in professional, technical, or creative services through online platforms like Fiverr and Upwork. One study found that when the transportation sector is omitted entirely, women make up a greater share of income-earners on digital platforms (which includes leasing, selling, transportation services, and non-transportation services). Among all four categories, the largest fraction of female digital earners was in selling.

One side note: some of Goldin’s work indicates that conventional ‘self-employment’ businesses in the 20th century were characterized by high time demands: these included owner-operated dentist, physician, optometrist, and pharmacist small business shops. As a result, when self-employment declined in these professions, it also led to a reduction in long and unpredictable hours, which was better for women. But technological changes have transformed the self-employment work context, and these new independent work opportunities are defined by their flexibility in contrast to conventional owner-operated small businesses.

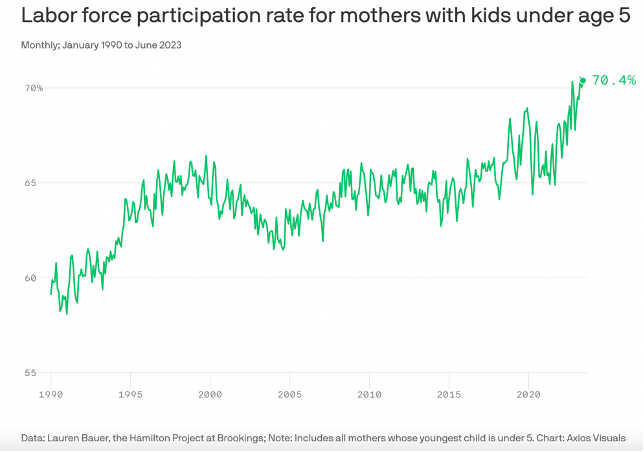

In today’s economy, both the rise in flexible arrangements offered through traditional employment and the rise of flexible jobs through non-traditional work arrangements are likely contributing to the new “highs” we are seeking with women’s labor force participation rate. As highlighted by a Brookings Institution study, since February 2023, the labor force participation rate for prime-age women—those between the ages of 25 and 54—has exceeded its all-time high.

What’s more is that the percentage of women in the workforce with young children is significantly higher than it has ever been.

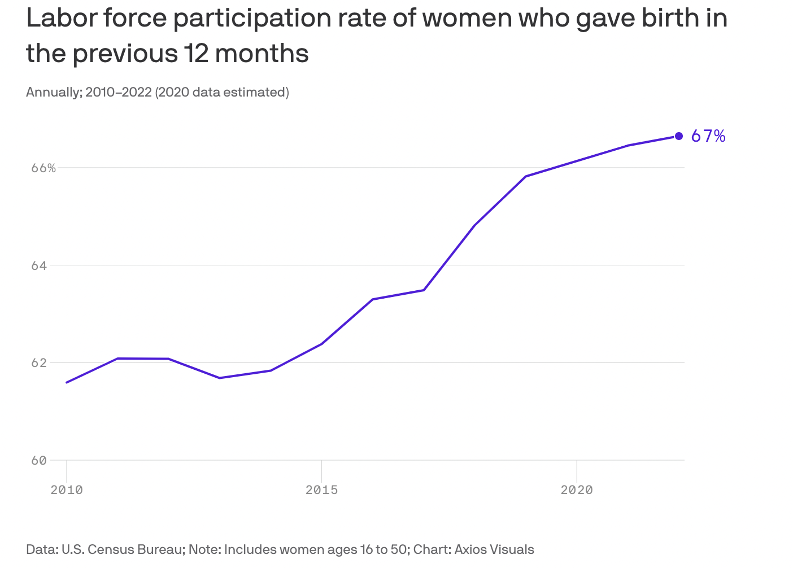

According to the latest American Community survey, 66.6% of U.S. women who gave birth in the previous 12 months were in the labor force as of 2022—another new high we’ve seen over the decades.

It will be interesting to monitor these trends in the coming years. And while flexible job arrangements are a key contributor here, more research is needed to isolate the other contributing factors that are leading to the greater participation of mothers in the workplace.

How to Encourage the Female Flexible Work Revolution

Technological changes that can better enable work-from-home or other flexible job arrangements will certainly help firms in offering greater flexibility in the workplace for employees. Managerial attitudes toward work-from-home arrangements will also help make this move more concrete.

But the real revolution for flexible work arrangements for women in the independent workforce will take-off when we break ancient regulations that tie benefits to only one type of work: employment. Many, many decades ago, tax incentives were created to encourage our fringe benefits to be tied to our traditional employment jobs, and labor laws were designed in a way that restricted the flow of benefits to non-traditional workers. Back then, this was not a big issue because most workers were traditional employees. But now that the circumstances have changed, these laws are failing a large sector of the workforce–a sector that provides significant work opportunities to women.

This creates an awkward trade-off for women and other independent workers who must choose between an inflexible employment job that comes with benefits and a flexible job that comes without benefits.

That does not have to be the case. State and federal policies could decouple benefits from traditional employment and allow access to benefits for all workers. Tying benefits to individuals rather than their employers could increase equity and efficiency. Indeed, several decades of economics research has highlighted how fringe benefits tied to your employer discourage job mobility and make labor markets more rigid. Fringe benefits that are tied to employers also increase the cost for exiting a particular job–thereby inadvertently creating a more monopsonistic market structure that reduces workers’ bargaining power by making workers more dependent on one particular firm.

The ultimate north star to decouple benefits from employment might be light-years away, but there can be marginal steps today toward this world. For example, this year Utah became the first state in the nation to explicitly remove some of the old-age barriers that prevent companies from freely offering benefits to independent workers. It was a simple and direct bill: don’t punish hiring parties that want to voluntarily provide benefits to independent workers. Of course, it will be crucial for federal policy to also make a move in this direction before we expect much in Utah. Still, Utah and other states can foster a fertile ground to enable small steps toward decoupling benefits from employment.

The bottom line: Flexibility is a staple feature of independent work today, and it offers income opportunities for a large set of working Americans who either desire or require more flexible forms of work. This is especially true for women, who have been driving the growth in the non-traditional workforce. And as Goldin’s research highlights, more flexibility in the workplace means better opportunities for working mothers.

At the same time, we need to fix the shortcomings that exist in these independent, flexible work arrangements—for example, workers do not have access to benefits afforded to traditional employees. This is because our system prioritizes the immobility of benefits (e.g., healthcare being tied to one employer) in a world where worker preferences have shifted and more value is placed on choice and portability.

To better meet the needs of the women in these independent work arrangements, federal and state governments could take steps to reform laws that would enable independent workers to have access to benefits.