Addressing Falling Fertility Rates With Flexible Work

Flexible work arrangements can help us address the looming demographic crisis, and make working mothers better off.

The demographic and fertility crisis in the United States has recently garnered significant attention. The fertility rate plummeted to an unprecedented low of 1.62 births per woman in 2023, far below the replacement level of 2.1 births per woman necessary to maintain a stable population. This trend started in the Great Depression and has only expedited, falling by over 20 percent between 2007 and 2020. It’s important to address falling birth rates, otherwise we will face a myriad of problems – from an aging population to a sovereign debt crisis.

The puzzle is that women do want to have more children. Women between the ages of 20-24 and born between 1995 and 1999 report wanting to have 2.1 children on average. This is essentially the same as women at the same age born in 1965-1969 who reported wanting 2.2 children. Declines in fertility instead seem to be driven by a decreasing likelihood of achieving earlier goals of having children or deferring childbearing until later in life, when having a greater number of children is more difficult.

The trend of women deferring childbearing began in the 1980s, with the advent of contraceptives and women’s career outcomes improved. With better opportunities ahead of them in the labor market, it became more costly for women to take time away from work.

Policymakers hoping to address the demographic crisis tend to focus on the monetary costs, but the real driver of falling fertility rates are higher opportunity costs. As women make more investments into their education and career, it becomes more “expensive” to take time away to have and raise children. Only focusing on the cost of childbearing misses a key part of the picture.

While being a working mother has become more accepted in recent years, in many ways it's become harder. Childcare has become more expensive and in shorter supply. Women are spending more time on childcare and on working outside the home than they did in the decades previous.

Many work cultures remain hostile to Mother’s caregiving responsibilities. It’s not surprising that, when including these costs in their calculations, many women choose to pursue furthering their education or their career over having children.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. More flexibility at work would allow women to better balance their desires to have successful careers and children.

When women have more flexibility at work, they tend to have more babies. COVID-19 provided a unique opportunity to test how worker flexibility would affect fertility and the relationship was positive. While many feared that COVID would bring a baby bust, it resulted in a small boom. This bump was especially pronounced for highly educated women, first births, and women under 25, pointing to women beginning their families sooner. While it seems counterintuitive to have babies at the height of a pandemic, the ability to work from home gave families more time to deal with the life changes that pregnancy and a new baby bring. In California, the fertility rate was 5.1% higher during the pandemic than it was prior.

This wasn’t the only time that more flexibility resulted in more babies. When broadband internet access was expanded in Germany between 2008 and 2021, more women worked from home which increased the likelihood they would have their desired number of children. Highly educated, 25-45 year old women chose to have more children after getting internet access because it gave them more flexibility.

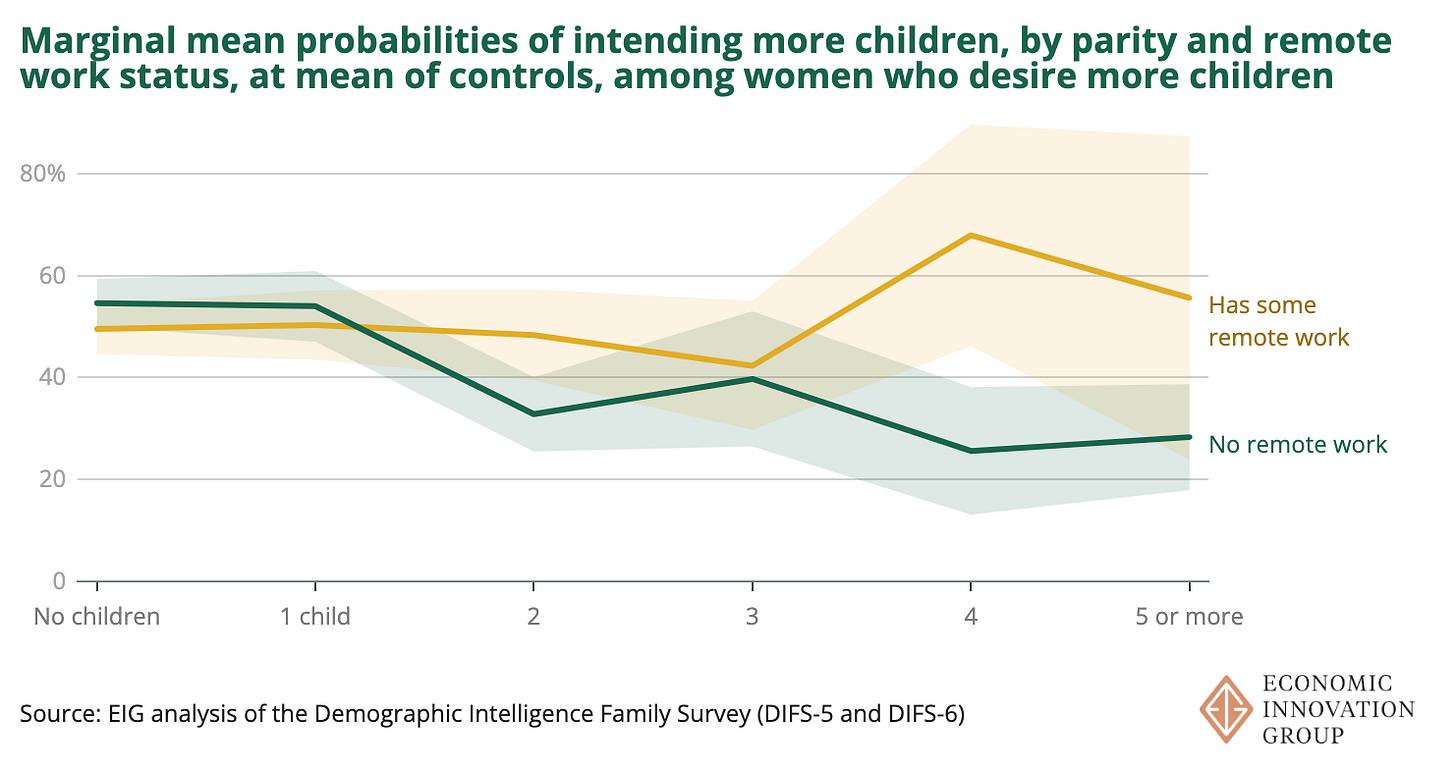

One study by the Economic Innovation Group found that while remote work doesn’t initiate childbearing, it may help women reach their “fertility goals,” or their desired number of children, by balancing the competing demands of work and family life. This is especially important because only about half of women achieve their fertility goals.

And fertility is just one benefit from worker flexibility. When women have flexible work arrangements their pay becomes more equal, they feel more satisfied with their work, have better mental and physical health, just to name a few. It should be no surprise that women desire this flexibility for their jobs – more so than men.

Worker flexibility isn’t a silver bullet solution to increasing fertility, but it would make it less costly for women to have children. Women shouldn’t be forced to choose between success at work and motherhood. Flexible work arrangements can help us address the looming demographic crisis, and make working mothers better off.