What is a “Good Job”?

And what is a good home? Just like calls for increasing the supply of housing, pro-worker advocates should focus on policies that increase the supply of a diverse set of jobs

There is growing rhetoric from the New Right and Progressive groups on how “America needs good jobs.” Few of these voices grapple with the inherent trade-offs in the characteristics of a “good job.” There is also little consensus on what those good job characteristics entail. Is a good job a unionized, factory job with steady hours and income, structured benefits, seniority as a means of promotion, but with few workplace flexibilities and opportunities for innovation and growth? For some, that sounds like winning the job lottery; for others, it is the definition of a nightmare job.

Or, is a good job a service-sector job that involves working with many different clients, a fluctuating schedule and income, little access to structured benefits and promotions, but with greater opportunities for flexibility, new initiatives, and growth? Someone like my dad, who grew up in the Soviet Union and felt stifled by the rigidity of the workplace, would call this job “a good job.” He would happily accept the trade-offs over a unionized job that offered steady hours and income, structured promotions, and greater access to benefits.

Calls for having “good jobs” are a lot like calls for building “good homes.” What is a good home? A rundown studio apartment in Manhattan with proximity to public transport and lively neighborhood amenities or a 5-bedroom house on a farm? Most of us would say “it depends on the person.” And beyond that, the same person may have preferred the studio in the city as a single, young professional, but would go for a farmhouse later in life when married with kids.

The same is true for job preferences. As a single, 22-year-old living in New York City, I may consider a “good job” working at a boot-strapped startup that is exciting and challenging with high-growth potential, but pays me mostly in equity, has me working 80 hours a week with few benefits, and offers me absolutely no job security–only the joy of knowing the startup could fail at any moment. But in 10 years when married with kids, I may prefer a steady and secure income at an established company.

The truth of the matter is that we should call for more jobs and for a diverse set of jobs to meet the diversity of wants and needs. Calls for “more housing” do not come with directives about the specific type of homes, but rather they focus on increasing the supply of homes—everywhere and of every kind. That’s because there are a diverse set of preferences for what is considered a “good home,” just like there are a diverse set of preferences for what is considered a “good job.”

Why Can’t We Have It All?

If a friend told you: “Well, I want a single home with 5-bedrooms, a large garden, but I want it to be in a lively neighborhood in Manhattan with close proximity to public transport, parks, and local restaurants.” – what would you say?

You might gently explain to your friend that we live in a world of trade-offs. There are not many of these luxury “unicorn” homes in Manhattan, and they tend to be out of the price range for the average American. So, when it comes to buying a home, we accept these trade-offs and have to make a choice between such characteristics like the size of the home vs. proximity to urban amenities.

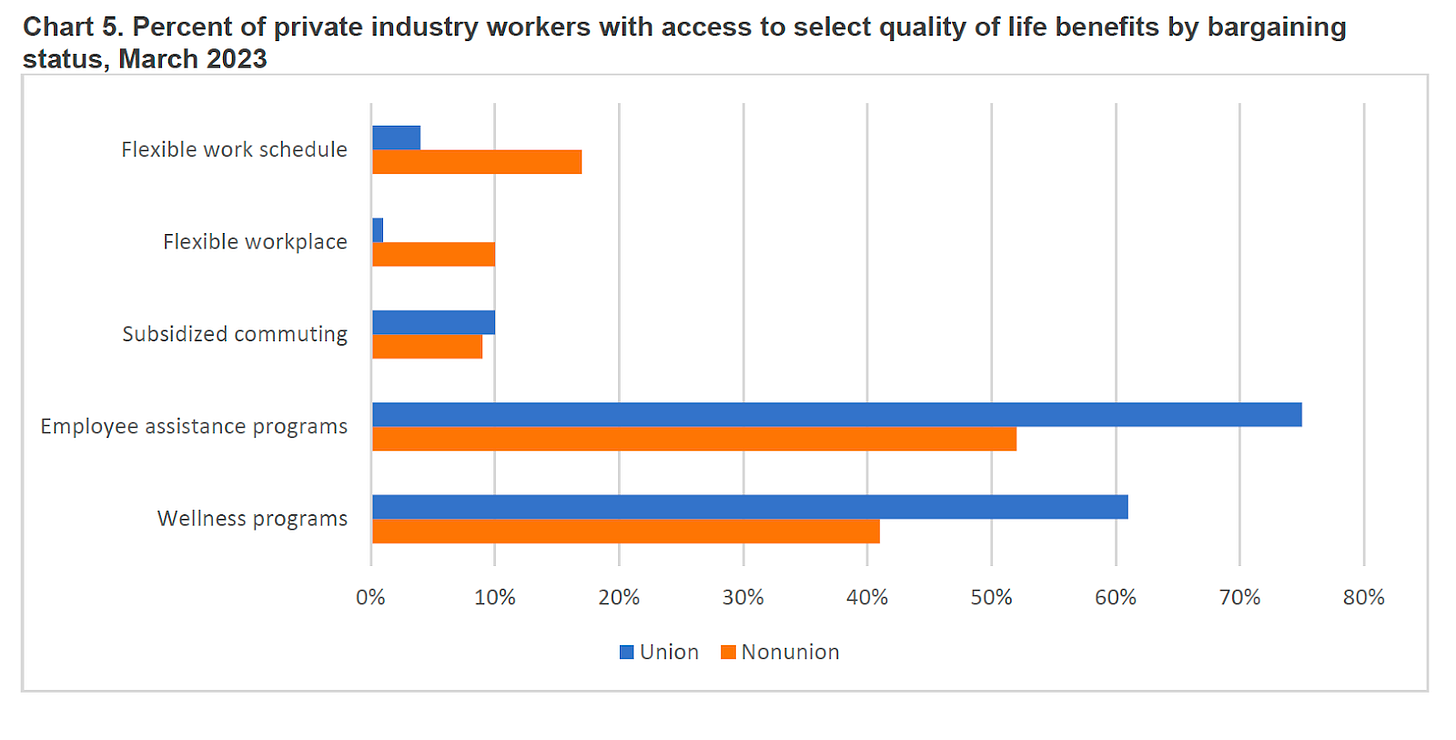

The same is true for jobs. A unionized job may come with greater access to some common workplace benefits, but may be boring and dull and not offer a key workplace amenity that many of us value today: flexibility. Take a look at the two charts below, published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics earlier this year.

While paid sick leave, paid holidays, and paid personal leave are more common in unionized jobs, access to flexible work schedules and flexible workplace benefits (as well as paid family leave) are more common in non-unionized jobs. Indeed, only 4 percent of union workers had access to a flexible work schedule, and a mere 1 percent had access to a flexible workplace.

In my post last week, I also highlighted the trade-offs that exist in working for small businesses and large companies. Large employers (with greater than 500 employees) are far more likely to pay you more, provide you with access to health insurance, and offer paid leave benefits (including paid parental leave).

But these “corporate America” jobs often come at the cost of working long hours, having a jerk for a boss, or doing dreadful or meaningless work. Some may prefer to work at a small business that offers a more relaxed work setting with great people, but these businesses will likely not pay as well or be as “secure” as your corporate or higher-education job.

Why Not Get Rid of the “Bad Jobs” (and the “Bad Homes”)?

So what about jobs that most would agree are “bad jobs”--jobs that don’t seem to have any compensating features? Jobs that pay minimum wage, don’t offer good benefits or workplace flexibility or real opportunities for growth, are often dull and meaningless, and where the bosses are still jerks to you.

These “bad jobs” remind me a lot of my first apartment in New York City when I was a graduate student. In a pre-WWII building, my apartment was the size of a luxurious walk-in closet and had no sink in the bathroom. Yes, you read that correctly: no sink in the bathroom. I also had the pleasure of hosting nightly cockroach visitors. And the best part: I paid $1,200 a month for it. A truly raw deal.

So why did I choose to live in this apartment for ants? It was in the heart of Greenwich Village and a 3-minute walk to NYU buildings where I spent most of my days. I was young, and it was my first time living in NYC: I wanted to be at the center of the universe. I was living on a graduate student budget, so my alternative was a bigger place that had a sink in the bathroom, but in Queens with a one-hour commute.

Similarly, in the labor market, a minimum wage job at McDonald’s is no one’s first choice. But if you’re a high school student who needs job experience and some money, it’s important that this job exists. It is in fact precisely because the McDonald’s job is no one’s first choice that you, the unskilled and inexperienced high school student who can only work a few hours a week, would easily be hired for this job.

Indeed, as the Bureau of Labor Statistics reports, although workers under 25 represent only a tiny fraction of hourly paid workers, they make up 44 percent of those paid the federal minimum wage or less. For many of these teenagers and young workers, this “bad job” may meet their needs better than the alternative of no job: a part-time job that will give you work experience and some money.

What is concerning about minimum-wage jobs from a policy perspective is if workers (especially those who have families to support) are often stuck in this type of job for a long time. Is it the case that most minimum-wage workers can’t seem to find better jobs and can’t seem to move up the wage ladder?

Studies highlight that a vast majority of minimum wage workers are “transitory” workers –meaning that when you sample them a few years later, you’ll find that they quickly moved into jobs that pay well above the minimum wage. But there are some workers who seem to have ‘minimum-wage careers.’ Demographic groups that generally have lower earnings are over-represented among such workers: women, minorities, and individuals with less education. A study of these minimum-wage careers concludes: “Thus, while relatively few in number, there is an identifiable subpopulation of workers whose lifetime income and employment is likely to be associated with minimum wages. For individuals in this group, minimum wages do not have merely transitory effects.”

In these cases, the problem is not that a “bad” minimum-wage job exists in your town. The problem is how to help increase opportunities for this group of workers who can’t seem to obtain better alternatives. The concern is now at least partially about the opportunities for workforce and skills development. It may also be a problem with the geographic location (e.g. a small town with a declining population that has few work opportunities) and the high costs associated with moving (which is also related to other things like cost of living, including housing).

In other words, the fact that I lived in my “ant” apartment for a year as a young graduate student is not a problem, neither is the fact that the dreadful apartment exists in the first place. In fact, the dreadful apartment unambiguously improved my life as a young, graduate student who otherwise could not afford to live in the center of the universe. The concern is when a family of four lives in that place for 10 years and can’t seem to find any other, better alternatives. Just as housing reform experts have advocated for increasing the supply of housing to help alleviate these problems, labor economists often advocate to focus on increasing the supply of jobs and creating an abundance of all types of work opportunities.

A Pro-Worker Policy Agenda Tip: Creating an Abundance of Diverse Work Opportunities

We should celebrate that our labor markets already provide a diverse set of work opportunities. Take a look at this partial list of the variety of jobs that already exist today:

A unionized private sector or public sector job with good and steady work hours, wages, benefits, and promotions

A high-paying job in a large corporation with some of the best benefits America has to offer

A “low-key” job at a local small business that provides a nice work-life balance and a lot of engagement with community, family, and friends

A meaningful job at a non-profit organization that inspires you everyday

An intensely challenging job at a startup that has exponential growth potential

A freelancing job that gives you maximum work flexibility

A gig economy job that gives you the opportunity to supplement your income after your 9-5pm job ends

A cashier job at a grocery store that allows you to get on-the-job experience while you’re working on your high school or college degrees

As this list illustrates, there are benefits to each one of these types of jobs (and each one of them comes with drawbacks, too). It is impossible to have a preconceived notion of what is a good job because whether the job is good or not depends on each person at each point of their lives.

Rather than aiming to make existing jobs meet some arbitrary definition of “a good job,” pro-worker advocates should focus on policies that can create a thriving labor market with an abundance and diversity of job opportunities to meet workers’ diverse wants and needs.