Labor’s Hidden Monopoly: Why the FTC Should Probe Union Power Too

The FTC's new focus on labor markets should include union monopoly power

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) recently announced a new directive to form a Joint Labor Markets Task Force aimed at addressing “unfair labor-market practices that harm American workers.” This initiative merges the FTC’s consumer protection and competition mandates to tackle a range of concerning practices in labor markets, from wage-fixing and no-poach agreements to noncompete clauses and labor market monopsonies.

While the FTC’s focus on anti-competitive behavior in labor markets is commendable, the directive should also include an important source of market concentration: powerful labor unions with monopolistic characteristics. Just as we should be concerned about corporate monopolies that harm consumers, we should also recognize that excessive union market power can lead to outcomes that harm workers.

When Labor Becomes Concentrated: The Case of America's Ports and Parcel Delivery

There is an inherent tension between competition and labor unions that has led to decades of legal controversies and judicial inconsistencies about whether certain union practices breach antitrust laws. The two examples below–dockworkers and UPS workers–illustrate how competition law is tested when just one or two powerful labor unions control a substantial share of an industry’s workforce.

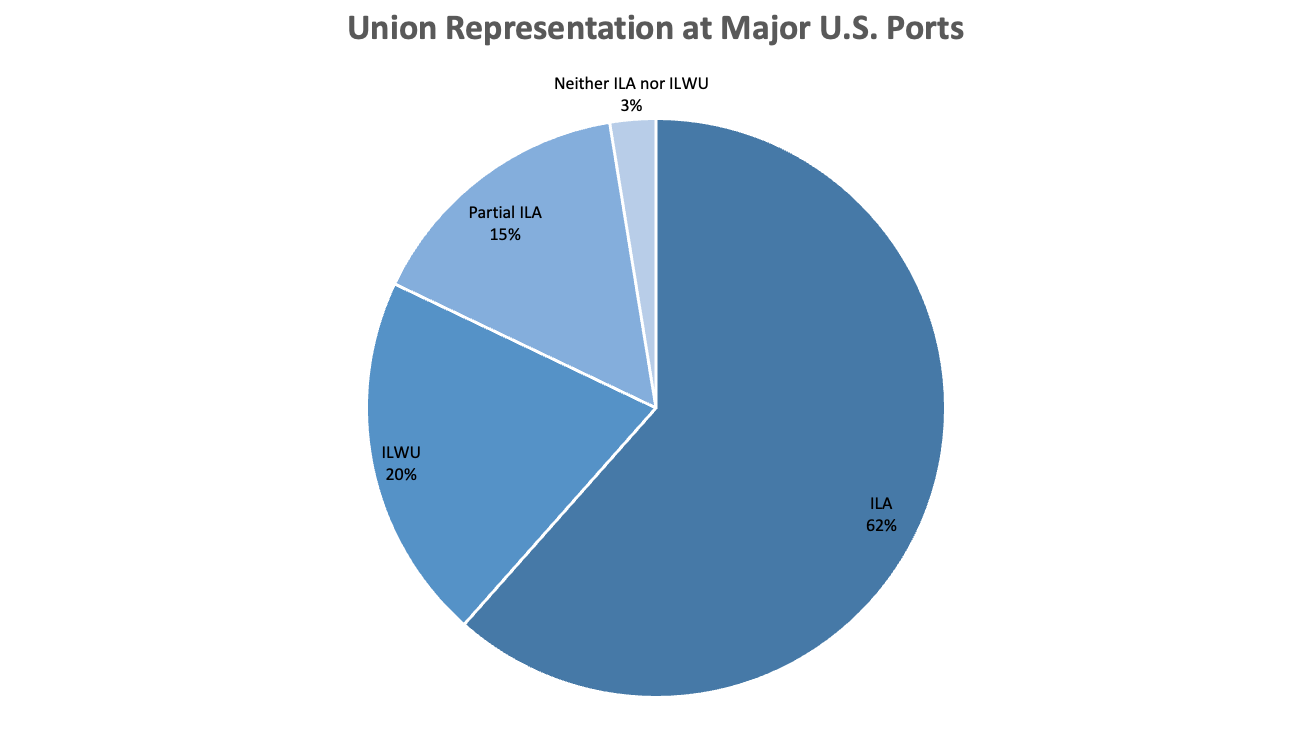

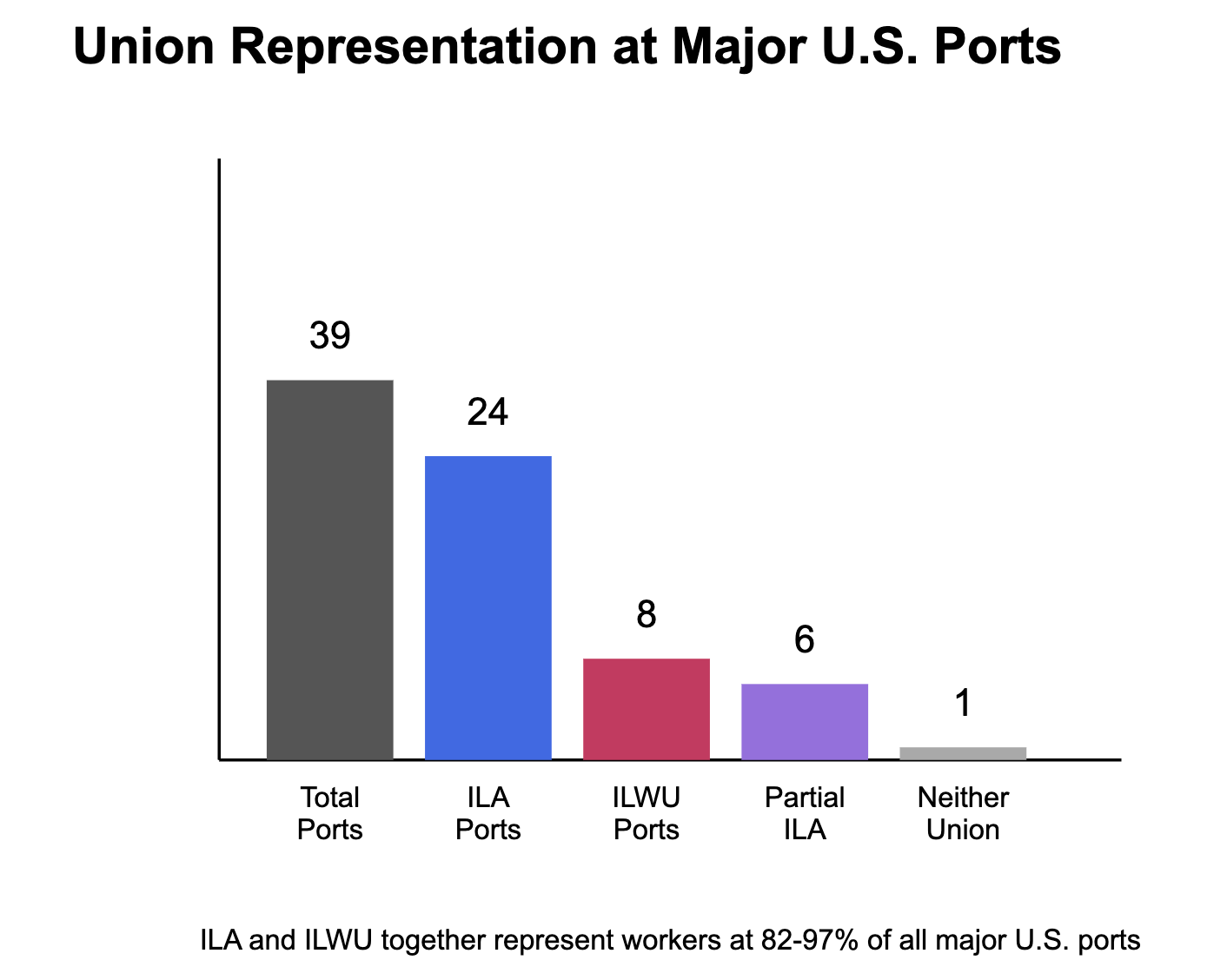

The first example is the case of dock workers. Currently, the International Longshoremen's Association (ILA) represents dockworkers at all major ports along the East and Gulf Coasts. Similarly, the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) represents workers at all major West Coast ports. Together, these two unions control labor at virtually all major U.S. ports—giving them extraordinary market power over the flow of goods throughout the economy.

Of the 39 major ports (Table 5) across the entirety of the United States, only 1 of them is not unionized by either ILA or ILWU. These two unions alone control labor representation at 97 percent of America's major ports. Even if ports with limited or partial ILA representation are excluded, these two unions still represent 82 percent of all major U.S. ports—a remarkably high concentration.

The ILA’s partial or limited representation refers to ports with one or more terminals that have ILA contracts (often for container or Ro-Ro cargo), while specialized bulk or petroleum terminals may be under other unions or non‑ union labor. These limited representation ports are typically in the Gulf or Great Lakes regions–for example, the ILA has limited presence at Corpus Christi because that port handles more petroleum and bulk cargo than containers.

Upon closer examination, we also see that 100 percent of all major U.S. ports on the East Coast are represented by one single union, the ILA. Likewise, on the West Coast, a single union—the ILWU—controls every major port. Such dominance clearly falls far short of any reasonable definition of a competitive market.

Other unions typically have much smaller representation in the dockworker category, often focusing on specialized roles or facilities. In fact, if we include all dockworkers across the U.S, ILA and ILWU remain the dominant unions, with approximately 85-90% of all unionized dockworkers belonging to one of these two organizations.

Furthermore, the ILA monopoly seems to also meet the “bad acts” requirement under antitrust laws. In October 2024, the ILA initiated a major strike not just to improve wages and benefits of workers, but also to ban any use of automation at the ports—including, even, automated gates. The ILA’s strike shut down every major port from Maine to Texas—a move its president described as an intentional way to “cripple the economy.” This isn't an exaggeration; when essential infrastructure is controlled by a single labor organization, the economic consequences of work stoppages can be dire.

We wouldn’t accept this behavior from corporate monopolies, yet we seem to overlook this behavior when it comes to labor union monopolies.

The International Brotherhood of Teamsters presents another striking example of labor market concentration. The union represents between 97 and 99 percent of all UPS workers that handle or transport packages (generally includes drivers, sorters, loaders, and administrative personnel at the company's operational facilities).1 According to recent data, the Teamsters’ membership at UPS now tops 340,000 workers, effectively accounting for over 98% of UPS’s total bargaining-unit employees.

This concentration of labor power in a single organization gives it substantial leverage not just over UPS, but over the entire ground delivery ecosystem.

These unions’ monopolistic control over critical sectors raises important questions about the balance between worker representation and market competition. While the FTC's directive identifies “labor market monopsonies” as harmful when created by employers, it should also acknowledge that similar concerns arise when labor organizations concentrate market power on the supply side.

The Evidence on Union Monopoly Power and Worker Outcomes

My new upcoming research (co-authored with our predoctoral researcher Revana Sharfuddin) on labor unions reveals that union monopoly power doesn't necessarily translate to better outcomes for workers. While powerful unions historically secured higher wages for their members, these apparent "big wins" at the bargaining table often came with significant trade-offs for workers.

The evidence shows that union monopoly power doesn’t just boost wages indefinitely; in fact, when unions push too hard, this backfires and results in slower employment growth and fewer job opportunities for unionized workers. Companies facing excessive union demands often cut investments—particularly in R&D and long-term capital—reducing productivity and profitability. This weakens businesses over time, increasing the likelihood of downsizing or closure, which ultimately leads to job losses and a smaller unionized workforce. These dynamics played out in the Rust Belt, where powerful unions and frequent labor conflicts were responsible for approximately 55% of the region's manufacturing employment decline.

The pattern continues today. After the Teamsters secured a significant contract for UPS workers in 2023, the company announced in early 2025 a “network reconfiguration” that “could result in the closure of up to 10 percent of our buildings... and a decrease in the size of our workforce.” Industry analysts estimate this may ultimately reduce UPS’s full-time headcount by nearly 10,000 positions, illustrating the potential cost of steep labor concessions. Similarly, Boeing faced a seven-week strike by the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers that cost the company $9.7 billion, followed by an announcement to cut 10% of its workforce.

These examples highlight a fundamental economic reality: When unions use their monopoly power to extract concessions that companies find unsustainable, workers often end up worse off through reduced employment opportunities.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. Several countries in Europe demonstrate that unions can be effective when they are more collaborative, flexible, moderate, and balanced–thereby mitigating the negative effects on workers while ensuring the long-term viability and survival of both the union and the company. As part of our upcoming study, we found that the monopolistic characteristics of labor unions are formed because of U.S. laws and bargaining structures. Indeed, in some European countries, labor unions are much less monopolistic and yet more pro-worker.

Applying Antitrust Principles to Labor Markets—Including Unions

The FTC’s new directive represents an opportunity to take a more comprehensive approach to labor market competition. Historically, labor unions received exemptions from antitrust laws through the Clayton Act of 1914 and the Norris-LaGuardia Act of 1932, which prioritized unions’ role in counterbalancing employer power.

However, the modern economy calls for a fresh assessment of how we balance worker representation with the benefits of competition. Just as the FTC scrutinizes corporate mergers that could harm consumer welfare, it should consider the anticompetitive effects when a single union controls a significant share of an industry's workforce.

Indeed, the FTC’s Bureau of Economics and Office of Policy Planning are both positioned to play a key role in researching labor markets to identify barriers to competition—including those created by government laws and regulations. By studying these dynamics, the FTC can publish research and spotlight how certain government-imposed rules or union protections may inadvertently stifle competition and harm workers.

To address unfair union monopoly practices and provide a more balanced approach, a new legislative framework is likely needed. What could it look like? Several possibilities merit consideration:

Limits on union market share: Perhaps we should reconsider allowing a single union to represent more than a certain percentage (say, 30-40%) of workers in a given sector. For instance, a cap on labor market share—similar to the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) used for corporate mergers—could be applied to ensure no single union far exceeds this threshold.

One simple variation of this principle could be as follows: Stipulate that one single union cannot represent two or more companies’ employees if antitrust laws would also prevent those same companies from merging.

FTC review of multi-employer bargaining units: When a single union negotiates with multiple employers simultaneously, this may function similarly to price-fixing arrangements that antitrust laws normally prohibit.

Restrictions on ‘most favored nation’ clauses: These provisions mandate uniform terms across employers, potentially stifling competition and innovation in labor markets.

Indeed, in many cases, courts and regulators have scrutinized ‘most favored nation’ clauses in labor agreements for anti-competitive effects, especially when they discourage employers from negotiating better deals with new labor entrants or competing unions.

Greater flexibility for employers to enter or exit multi-employer bargaining arrangements: This would enhance competition while preserving workers' collective bargaining rights.

A Path Forward for Competitive Labor Markets

Workers deserve both fair treatment and robust work opportunities. The evidence in our upcoming study suggests that moderate union power—characterized by balanced demands and increased flexibility—better preserves the benefits of collective bargaining while avoiding the downsides of monopolistic union behavior.

The FTC’s new Labor Markets Task Force presents an opportunity to take a truly comprehensive approach to labor market competition. By acknowledging that anti-competitive behavior can come from both employers and labor organizations, the FTC can develop policies that protect workers not just from anti-competitive corporate behavior, but also from the harmful effects of labor market concentration.

If we truly want pro-worker policies, we need to recognize that concentrated power—whether wielded by corporations or unions—rarely benefits workers in the long run. True pro-worker policy embraces both fair representation and healthy competition in labor markets.

This is an estimation based on my calculations from the latest UPS annual report for share-owners and the Teamsters’ public statements

You're conveniently ignoring the fact that from 1954 to 2022 union membership dropped from 33.5% to 10.1%. As well as the academic evidence on market conentration increasing over time. The fact that you don't analyse these trends makes this article seem like its pushing a political agenda.